If Einstein Had The Internet: An Interview With Balaji Srinivasan

Technology as determinant of historical cycles in market and government influence, why culture has stagnated despite advances in the tools that make it, how wokism will lose, and more!

Balaji is a former General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz and former CTO of Coinbase, cofounder of Earn, Counsyl, Teleport, and Coin Center, renowned angel investor, and the only thinker online who matters—with Andreessen Horowitz cofounder Ben Horowitz describing him as “Einstein if he had internet access.” He holds a BS, MS, and PhD in Electrical Engineering and an MS in Chemical Engineering from Stanford, though he thinks offline colleges are now obsolete educational technology and would advise young people to do an ISA or a startup instead. I have no idea how one person can achieve so much but I’d like to figure out how, and I’m sure everyone else would too so we’ll figure it out together. To avoid being overtaken by the future, follow him and turn his notifications on via twitter.com/balajis and subscribe to his new project at 1729.com for more.

My first question for you is one I posed recently in a conversation with Marc Andreessen, which was inspired by the common sentiment from the activist-class that non-engagement in politics is the same as working against human progress: Almost all technological advances and improvements to quality of life seen over the last half-century have found their way to the public from the private sector. While the same ineffectual debates over equal opportunities in education, employment, and healthcare have happened in congress for decades, the private sector has made university-level learning accessible and free, employs over 70% of all Americans, and inches nearer every year to making death optional. I’m uncertain whether we need politics at all with a market so apt at solving problems and would even like to think issues like race in the United States may be amenable to a market solution. Is it reasonable for me to think so broadly about what the market can do?

Well, lots to talk about here.

Technology is the Driving Force of History

First, I generally agree with the thrust of your question. But I think we often discuss these things in kind of a flatland-ish way, as a projection down onto a few dimensions (politics and the market and so on), which do make sense, but that don’t always lead to conclusions about why one force is triumphing over the other today when it lost ground in the past. Why, for example, is the market (SpaceX, Blue Origin) now driving space exploration when it used to be politics (Sputnik, NASA) in the 50s and 60s? Why were political leaders both willing and able to crush market forces in the early 20th century (Stalin, Roosevelt, etc), only to U-turn completely by the late 20th century (Reagan, Gorbachev, Thatcher, Deng Xiaoping, Manmohan Singh)?

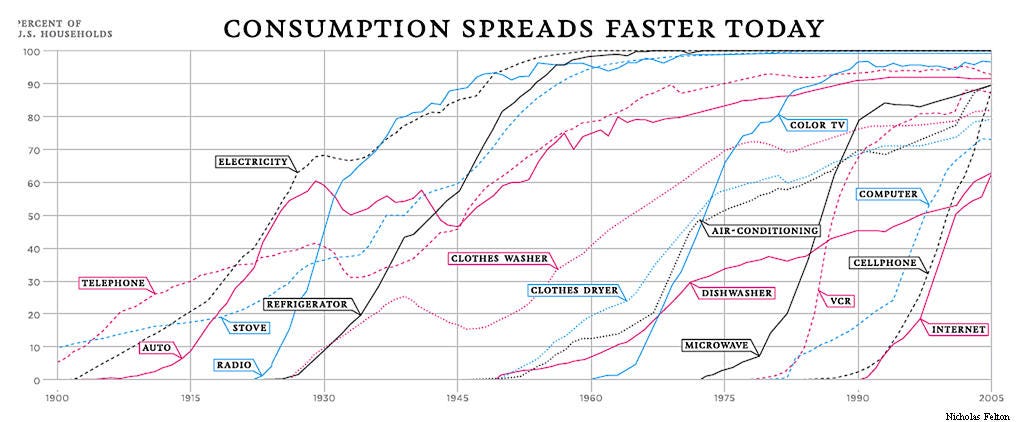

My high-level answer is that technology is the driving force of history. Technology favored centralization in the US from arguably 1754-1947 (join or die in the French and Indian War, unified national government post-Civil War, railroads, telegraph, radio, television, movies, mass media in general, and mass production) and is now favoring decentralization from roughly 1947 to the present day (transistor, personal computer, internet, remote work, smartphone, cryptocurrency).

This thesis isn’t wholly original to me, of course — you can see major pieces of it in books like the Sovereign Individual, The Singularity is Near, Snow Crash, Ready Player One, and sci-fi in general. Indeed, the entire premise of sci-fi is that a new scientific invention has changed the world, though we only seem to fully understand that in the context of a movie (where the changes are often for the worse and happen in fast-forward montages), but not in the context of the world today (where the changes are often for the better and happen one day at a time).

Put another way, science and technology aren’t the main headlines of our day, politics and crime are — even if the former is where most of our attention should be. This too may be just a 20th century hangover, a time when politico-verbal matters took center stage over techno-economic affairs. But as the driving force of history, as the throughline of history, one perspective is that regimes rise and fall, that Ozymandias types eventually fall into oblivion, but technology is (so far!) up and to the right. And that what distinguishes man from ape is technology.

Anyway, from this vantage point, many of the ideas on how to organize human society have been around forever, but technologies make them feasible and infeasible by turns. A political ideology that requires total centralized control may seem unstoppable when technology favors this...and then may become untenable when innovation turns things in the direction of decentralization.

So in this view it is technology that is the driving force of history, and it is this force, this z-axis vantage point, that we can use to look down upon both politics and the market.

A related meta-framework, before answering your question, is that there are now not one but three Leviathans in a Hobbes-like sense. Three forces that hover over fallible men that make them behave in pro-social ways: God, State, and Network.

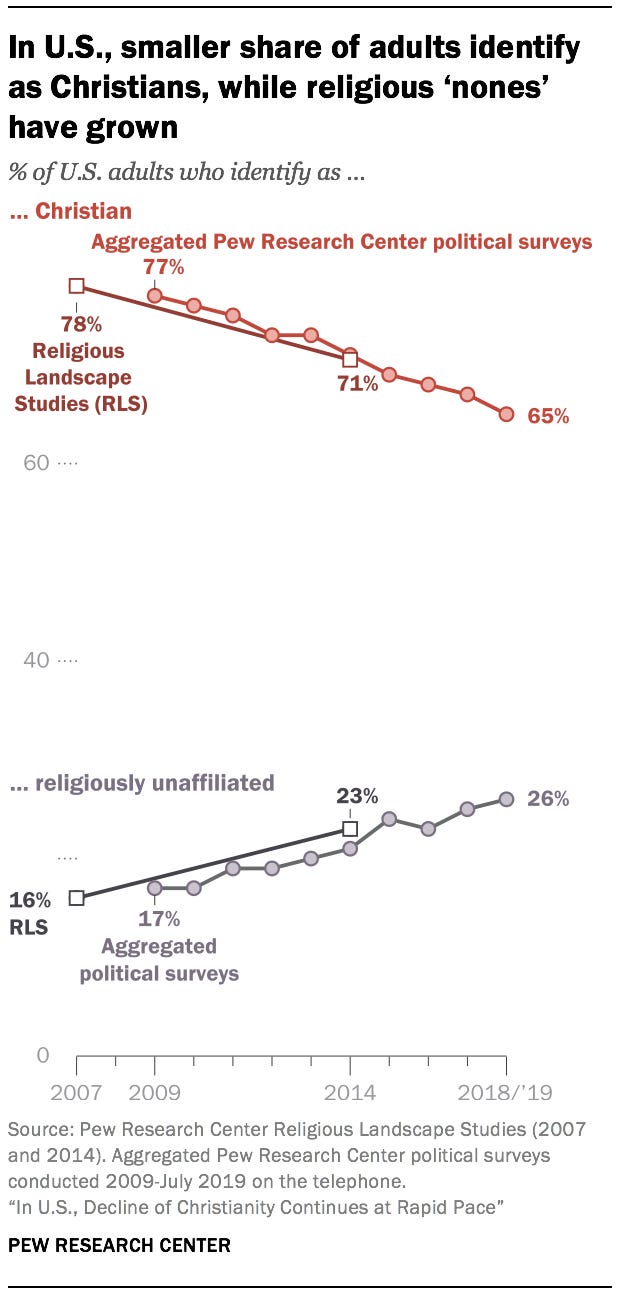

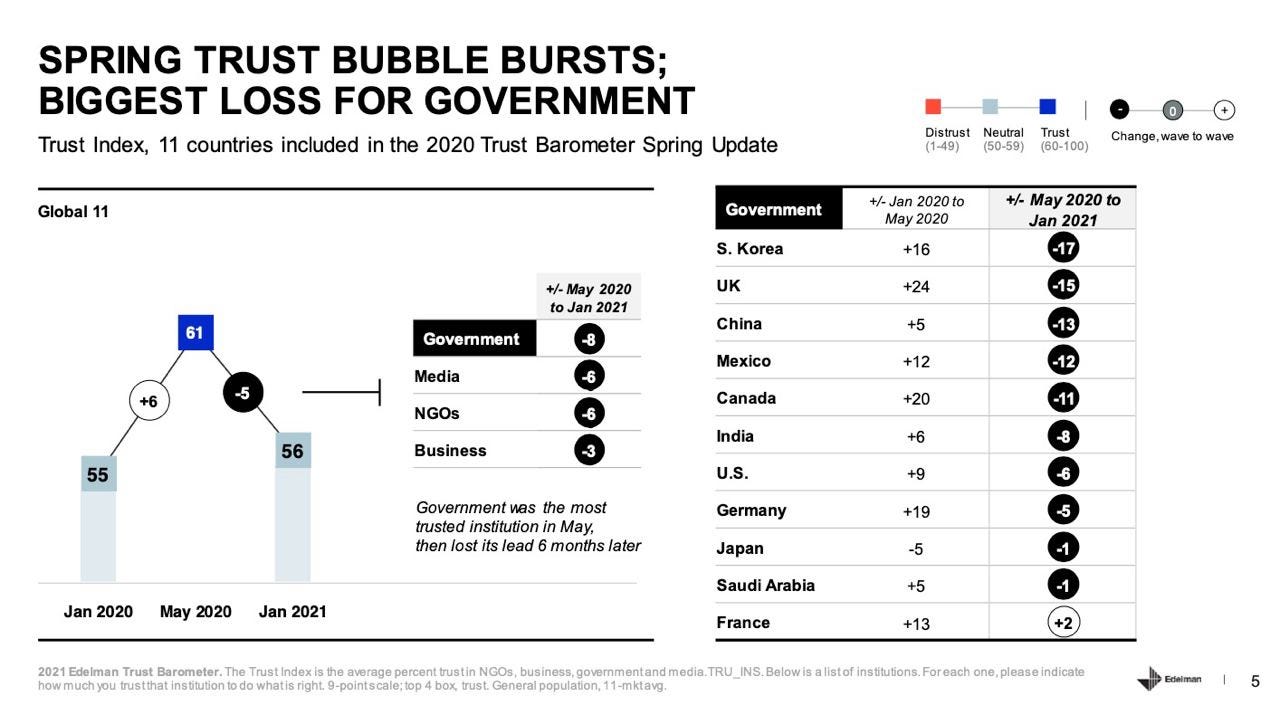

The first Leviathan was God. In the 1800s, people didn’t steal because they actually feared God. They believed in a way that’s hard for us to understand, they thought of God as an active force in the world, firing-and-brimstoning away. They wanted god-fearing men in power, because a man who genuinely believed in God would behave well even if no one could punish him. That is, a powerful leader who actually believed that eternal damnation was the punishment for violating religious edicts could be relied upon by the public even if no human could see whether he had misbehaved. At least, this is a rational retrofitting of why being genuinely “god-fearing” was important to people, though they might not articulate it in quite that way. God was the ultimate force, the Leviathan.

By the late 1800s/early 1900s, Nietzsche wrote that “God is dead”. What he meant is that a critical mass of the intelligentsia didn’t believe in God anymore, not in the same way their forefathers did. So a new Leviathan now rose to pre-eminence, one that existed before but gained new significance: the State. And so in the 1900s, why didn’t you steal? Because even if you didn’t believe in God, the State would punish you. The full global displacement of God by the State (something already clearly underway in France since 1789) led to the giant wars of the 20th century, Democratic Capitalism vs Nazism vs Communism. These new faiths replaced g-o-d with g-o-v, faiths which centered the State over God as the most powerful force on earth.

That brings us to the present:

Now, today, as the graphs above show it is not just God that is dead. It is the State that is dying. Because here in the early innings of the 21st century, faith in the State is plummeting. Faith in God has crashed too, though there may be some inchoate revival of religious faith pending. But it is the Network that is the next Leviathan.

The Network is the next Leviathan

By the Network I mean the computer network, the social network, the internet, and now the crypto network. In the 1800s you wouldn’t steal because God would smite you, in the 1900s you didn’t steal because the State would punish you, but in the 2000s you can’t steal because the Network won’t let you. Either the social network will mob you, or the cryptocurrency network won’t let you steal because you lack the private key, or both.

Put another way, what’s the most powerful force on earth? In the 1800s, God. In the 1900s, the US military. And by the mid-2000s, encryption. Because as Assange put it, no amount of violence can solve certain kinds of math problems. So it doesn’t matter how many nuclear weapons you have; if property or information is secured by cryptography, the state can’t seize it without getting the solution to an equation.

Now, the obvious response is that a state like Venezuela can still try to beat someone up to get that solution, put the proverbial gun to their head to get their password and private keys — but first they’ll have to find that person’s offline identity, map it to a physical location, establish that they have jurisdiction, send in the (expensive) special forces, and do this to an endless number of people in an endless number of locations, while dealing with various complications like anonymous remailers, multisigs, zero-knowledge, dead-man’s switches, and timelocks. So at a minimum, encryption increases the cost of state coercion. In other words, seizing Bitcoin is not quite as easy as inflating a fiat currency. It’s not something a hostile state like Venezuela can seize en masse with a keypress, they need to go house-by-house. And the history of Satoshi Nakamoto’s successful maintenance of pseudonymity, of Apple’s partial thwarting of the FBI, and of the Bitcoin network’s resilience to the Chinese state’s mining shutdown show that the Network’s pseudonymity and cryptography are already partially obstructing at least some of the State’s surveillance and violence.

Encryption thus limits governments in a way no legislation can. And as described at length in this piece, it’s not just about protection of private property. It’s about using encryption and crypto to protect freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of contract, prevention from discrimination and cancellation via pseudonymity, individual privacy, and truly equal protection under rule-of-code — even as the State’s paper-based guarantees of the same become ever more hollow.

In this sense, the Network is the next Leviathan, because on key dimensions it is becoming more powerful and more just than the State. The computer always gives the same output given the same input code, unlike the fallible human judiciary with its error-prone (or politicized) enforcement of the law.

Hybrids: God/State, God/Network, God/State/Network, Network/State

The three forces above (God, State, Network) aren’t just pure forms. You can remix them together.

God/State: the mid-century US was “for god and country”, and it combated the USSR, which was the pure State.

God/Network: this would be something like the Jewish diaspora before Israel, or the Mormons, or any religious diaspora connected by some kind of communications network.

God/State/Network - this is something like the Jewish diaspora after Israel.

This brings me to the fusion I’m most interested in: The Network State, a combination of the State and the Network. And there are a few different ways to get to a Network State.

In one approach, a state takes on the capabilities of a software company and software CEO, and fuses with the network. In different ways, this is what is happening in Estonia, Singapore, and Dubai, and perhaps in the US in an existing place like Miami or a new startup city like Culdesac, Arizona or Starbase, Texas. This is the path by which a startup city eventually becomes a Network State.

Another way is for an internet leader to build a large enough community online that it can crowdfund territory, as per this essay on Network Unions and this one on Network States. We haven’t yet observed this at large scale, but I think it’s going to happen this decade. This is the good version of the Network State, the one people will flock to.

The malign version of the Network State is what is happening in China, and in America at the federal level with the tech crackdowns. In both countries, the establishment is inventing rationales to essentially seize previously founder-controlled companies from above. In China the recipe was (a) a few years of media demonization plus (b) mandatory Xi Jinping thought sessions followed by (c) decapitation and quasi-nationalization — as is happening with Alibaba and ByteDance. In America it’s very similar: (a) a few years of media demonization plus (b) quasi-mandatory wokeness within followed by (c) anti-trust, regulation, and quasi-nationalization. Sometimes the decapitation is forceful (Uber was an early target here) and sometimes it’s quasi-voluntary. One thesis on why many of the major tech founders have stepped down, other than Zuck and Jack, is that they don’t want to become personally demonized during the no-win antitrust process.

Anyway, in both cases the State is “acquiring” centralized technology companies at gunpoint, fusing with the Network from above.

Whatever the surface justification, these are hostile takeovers of centralized tech companies by centralized states. And once taken over, these companies will be turned into total surveillance machines and tools of social control. In China perhaps this is already obvious. But in America anti-trust will mean zero trust; in the aftermath of any ostensibly “economic” settlement the national security state will get everything it ever wanted in terms of backdoors to Google and Facebook. The NSA won’t need to hack its way in, it’ll get a front door. And then it will likely get hacked in turn, spraying all of your data over the internet. This is the bad version of the Network State, the one people want to exit from.

Now, with these concepts, let’s go through your question, piece by piece.

> which was inspired by the common sentiment from the activist-class that non-engagement in politics is the same as working against human progress:

I actually kind of agree with the activist class, but for a different reason. If technological progressives don’t figure out how to change legal structures, we’ll keep getting more COVID-19s, episodes where the nepotistic establishment of the East Coast of the United States is both in power and out of their depth.

Technological Progressive vs Technological Conservative

What do I mean by “technological progressives”? You can think of the “people of the Network” as technological progressives, and the “people of the State” as political progressives (charitably) or technological conservatives (perhaps more realistically).

Both are often aligned at the high level on the goal of solving a problem like eradicating COVID-19, building housing, or reducing car crashes. But the people of the Network usually start by writing code and thinking about individual volition, whereas for the people of the State the first recourse is passing laws and collective coercion.

Put another way, the people of the Network start by thinking about getting a *piece of the network* to call their own. A domain name, something they can build up from scratch, starting with a bare website like reddit.com and ending up with a massive online destination that everyone voluntarily seeks out. The primary goal of the technological progressive, the tech founder is to build — and for no one to have power over them.

By contrast the people of the State start by thinking about capturing a *piece of the state*. To win an election, to influence legislation via a nonprofit, to write an article that has “impact” in the sense of impacting policy, to be appointed Undersecretary of something or other...this is their mindset. The goal is to get a piece of this gigantic baton that is the government, to get a club to coerce people (for their own good of course), to maybe get a little budget along the way, and to finally “change the world” by changing the policy. To make something that was previously discretionary either mandatory or forbidden, to redirect the flow of printed money, to exert force through the law. The primary goal of the political progressive is thus the opposite of the technological progressive: their goal, verbalized or not, conscious or not, is to exert power over others.

Now, this is a caricature. Of course there are good people of the State, just like there are bad people of the Network. It is possible to use a minimal amount of coercion for good against genuinely bad actors; this truth is the difference between minarchism and anarchism.

But obviously, these worldviews collide. One group wants no one to have power over them; the other seeks to exert power over others. One way I see this being resolved is that the people of the State use the club of the law to smash American tech over the next decade, thereby gaining more power domestically. But tech has already gone global thanks to remote work, and most technologists are immigrants already...so the people of the Network simply shift their attention overseas — or don’t come in the first place. So the federal action merely drives away immigrant founders, and the State loses power on a global scale. (Local and state governments in the US may respond differently, which is an intriguing twist).

The same thing is also happening in China, by the way, where the most able technologists are alighting for new countries — and no longer coming to the US, where they aren’t welcome anyway.

How should the Network engage with the State?

No matter how it’s resolved, the activists in your quote are actually right in a sense (“non-engagement in politics is the same as working against human progress”). If the people of the Network don’t engage in politics in some way, they actually are working against human progress. See this tweet, for example. It’s because we left the State to people who can only inherit and can’t build that we got the current state of San Francisco, California, USA.

The people of the Network can build a billion dollar business from a computer, but we can’t build a shed in SF without a billion permits. It is this State regulation of the physical world (and the accompanying risk aversion/conformism) which is why we don’t have fusion power or flying cars, full stop. Thiel, Cowen, and J Storrs Hall are all excellent on this. I think an essay of mine (“Regulation, Disruption, and the Technologies of 2013”) also holds up reasonably well, and it’s also worth looking at wtfhappenedin1971.com, which credibly pins at least some of the blame on going off the gold standard.

The Network has given us ways to partially work around these limitations of the State. We can innovate in bits without innovating in atoms, build in the cloud even when we can’t on the land.

But as noted, the people of the State control atoms, and are increasingly going to use that control to try to regulate bits. Hence the comical-yet-dangerous EU “AI regulations” which seek to regulate the use of logic itself, in a fashion reminiscent of Harrison Bergeron.

So, regarding this part of your inquiry, the question is whether the (good) people of the Network will yet find a way to use bits to outmaneuver the (bad) people of the State, and reopen innovation in atoms — which will benefit both them and us, not that they’ll ever give us credit for it. One set of ideas involves collaborating with the *good* people of the State worldwide, who do exist, and is outlined here, here, here, and here.

> Almost all technological advances and improvements to quality of life seen over the last half-century have found their way to the public from the private sector.

Yes. But the framework above gives some rationale as to why that is so — why did it start in the public sector, and why did it shift? Because technology no longer favors 20th-century-style centralized states, and new models are now arising. However, there was a period from ~1933-1970 when the centralized US government did the Hoover Dam, the Manhattan Project, and the Moon Landing. The transistor and early internet came out of this era as well. And there were some later things also catalyzed by the State (albeit often by non-bureaucrats who managed to commandeer bureaucrat funds) like the Human Genome Project and the self-driving car which came out of the public sector.

This period was real, but in overstated form it has become the basis for books like Mazzucato’s Entrepreneurial State — which I disagree with, and which Mingardi and McCloskey have rebutted at length in the Myth of the Entrepreneurial State.

The reason I disagree with the “Entrepreneurial State” concept is that:

The name itself is oxymoronic. As macroeconomists never tire of telling us, governments aren’t households, because unlike actual entrepreneurs the state can seize funds and print money. So there is no financial risk, and hence nothing of “entrepreneurship” in the entrepreneurial state.

The book doesn’t consider the fact that most math/physics/etc was invented prior to the founding of NSF, and therefore doesn’t need NSF to exist

It doesn’t take into account the waxing and waning of centralized state capacity due to technology

It doesn’t contend with the slowdown in physical world innovation that has happened during the post-1970 period, which Thiel, Cowen, and J Storrs Hall have all documented

It doesn’t look at how difficult VC or angel investing actually is, so it doesn’t really ask whether those “investments” by the state had real returns

Most importantly, it doesn’t engage with the counterfactual of what would happen if we had many independent funding sources, rather than a single centralized state

But it’s true that there was a period mid-century where all other actors besides the US and USSR were squashed down and centralized states dominated innovation. I wouldn’t say it’s because they were necessarily better at innovating, but they were better at dominating due to the centralized tech of that time. It was more about the Enormous State than the Entrepreneurial State.

>While the same ineffectual debates over equal opportunities in education, employment, and healthcare have happened in congress for decades, the private sector has made university-level learning accessible and free, employs over 70% of all Americans, and inches nearer every year to making death optional. I’m uncertain whether we need politics at all with a market so apt at solving problems and would even like to think issues like race in the United States may be amenable to a market solution. Is it reasonable for me to think so broadly about what the market can do?

So, now all our preliminaries pay some dividends. I think if you replace “politics” with the State and “market” with the Network — yes, it is reasonable for you to think so broadly about what the Network can do, because the Network is the next Leviathan, and it is in key respects becoming more powerful than the State.

On the specific question of race, which American society is currently obsessed with, and which you and I both as “people of color” have an interest in...I think we’re actually about to enter a Pseudonymous Economy where it won’t even be possible to discriminate against or cancel someone — because they’ll have AI-generated faces, video, audio, accents, and even language.

And you’ll trade with them in crypto, and it’ll be considered a faux-pas (and perhaps eventually a legal issue) to ask them any questions about their actual appearance. Cryptography will be the way to prove things online, rather than simple assertion. Videos can be faked, no one will know what anyone looks like, but with cryptography we can furnish a proof-of-X or Y.

My next question is about the creation of culture, which (counterintuitively) has failed to keep pace with advances in technology over the last few decades and has now become virtually stagnant. Throughout all of history the cultural development of a civilization can be traced by the stories it generated for itself, and our own storytelling medium, film, suggests to me that the era of contemporary cultural innovation is far behind us, with the most ambitious works being made around the 90s and a bit before (Clueless, Pulp Fiction, Jurassic Park, The Truman Show, The Matrix, Eyes Wide Shut, Being John Malkovich, Fight Club, Titanic, The Lion King, Gattaca, Terminator, Blade Runner, Back To The Future, Rain Man, Star Wars), and with the industry now mining the past for ideas ad nauseam, with the same trend away from novelty being seen in nearly all other forms of culture-making. Why has cultural development failed to keep pace with advances in the tools used to generate it? Social anthropologist J.D. Unwin proposes in Sex and Culture that the loosening of sexual mores has a dispersive effect on the creative energies in a society, while others hold responsible the drop in IQ seen over the last few decades or the outsourcing of cognitive functions to our devices with diminishing returns on attention, and I wonder if the key to explaining the decline of our culture-producing institutions can be found here? Is it that cultural creation at scale may be impossible when the market can supply content for every hyper-specific niche, or just that creative industries have gone the way of competition-starved monopolies?

A shorter answer this time :)

First, I think your observation is right. Many more films are remakes now; here’s some links showing it.

It’s not just about remakes. Aesthetically as well, for roughly the last 10 years at least, Hollywood has used the orange-and-blue aesthetic to make things look cinematic. So even the ones that aren’t sequels look the same:

Second, an interesting point is that the best movies of the 90s (and early 2000s) like The Matrix, Memento, the Truman Show, Fight Club, the Game, 12 Monkeys, Dark City, and the Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind — actually had quite a few movies about a constructed reality where our memories aren’t real. Almost like we were waking up from a long centralized slumber...

Third, there’s an argument to be made that clothes have also mostly stayed static for the last 20 years. I think we can instantly pinpoint the 50s look (square), the 60s look (tie dye), the 70s look (bell bottoms), the 80s look (big hair), and the 90s look (grunge)...but can we instantly pinpoint the difference between the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s? More body modifications, for sure, but in terms of attire and hair...feels like there isn’t a single word like “hippy” or “grunge” for the style of those eras. This is not my area at all, but it feels like physical fashion is less era-defining than it used to be. Our fashions are increasingly digital; you might not be able to tell late 90s clothes from 10s clothes as easily as you can distinguish clothes from the 70s and 50s, but you can certainly distinguish the websites from these eras.

Fourth, as centralized culture creation in film and clothes and the like has sort of sputtered to a halt, all culture creation has moved online. The less interesting version of this is that streaming serial TV shows are better written than mass market Hollywood shows. The more interesting version is that Reddit, Twitter, Hacker News, and the like have become bottom-up culture creation factories. Movements like keto, intermittent fasting/OMAD, LEANFire, cryptocurrency, DIYBio, and meme culture..all of these arose from organic subcommunities online.

Fifth, since the whole SOPA/PIPA thing from 9 years ago, Silicon Valley has basically acquired/merged with Hollywood. It’s taken several years to fully digest that acquisition [which hasn’t really been written up], but I think we are about to see the full fruits of internet native Hollywood, which is much bigger than the old Hollywood. I can elaborate on this.

So, putting it together, to answer your q, why has culture creation failed to keep up with tech? I think it’s a little like the electric dynamo, where there’s a bit of a lag as people digest the technology shock, and then production massively accelerates. I think this is the decade of professionalized, decentralized culture creation. Should I elaborate on that too?

Yes! Please elaborate further. (As a stipulation, I want to add: Culture producing institutions along with the institutions that fund them have experienced capture in recent years by a form of communism developed by the successor of Antonio Gramsci, Herbert Marcuse, who substituted the traditional rhetoric of class-struggle with the struggles of race, sex, and gender. Your view of the future is so much more optimistic than I’ve been able to feel in a long time because it presupposes the defeat of woke communist bullshit in the end, and I’m interested to know and want to be inspired by how you see that all happening).

One comment: as you are aware, wokeness isn’t the same as communism. But you’re right that it has certain similarities. And the understanding of these similarities (and differences) is key to defeating it. For example, if communism was the redistribution of wealth, wokeness is the redistribution of status. And if communism purported to benefit workers and peasants (but was eventually horrible for them, and everyone), wokeness purports to benefit women and people of color (yet is horrible for us as “people of color”, and for everyone).

Now, communism did eventually lose. But it didn’t just lose, it was beaten by an alternate set of American institutions that outlasted and outproduced it. And it took decades. So, how do we defeat wokeness? It’s going to require something at that level.

The short recipe is that we need to build parallel institutions that are not just the equal but the superior of the institutions that wokes have captured and corrupted. Crypto shows the way, with Bitcoin as the exit from the Fed, and Ethereum as the replacement for Wall Street. But we’ll also need an alternative to Harvard, and Hollywood, and the legacy media, and the whole alphabet soup of regulatory agencies. Fortunately that’s what founders specialize in doing: building better alternatives.

Building these alternatives requires a recognition that we’ll have to work across borders, we’ll have to collaborate globally, because wokeness is unfortunately as American as communism was Russian. That is, even if it started as an international revolutionary movement with significant German and American contributions, in many ways communism under the Soviets became a Russian nationalist project. Stalin turned it into an ideological justification for expanding the boundaries of what was once the Russian empire. In their own way, the Soviets (like their former Nazi allies) were also seeking lebensraum — just for Russians rather than Germans, and in the name of Stalinist socialist nationalism rather than Hitlerian nationalist socialism. For example, as Stalin expanded the USSR, smaller ethnic groups like the Estonians had their culture and language crushed for generations by Russophones, in the name of liberating their working class.

Today, just like communism served as justification for Russian imperialism, wokeness serves as justification for US imperialism. You see this when you watch military recruitment videos that implicitly justify the use of force by praising themselves in woke language, or when you see Raytheon talk about civil rights. And when you’re abroad, it’s even more obvious that wokeness is not indigenous — the carriers of this mind virus always somehow hail from American universities and quote from American media.

A great example of woke imperialism was a recent foofaraw in which a woke tried to cancel someone for naming a protocol “AAVE”. The idea was that the authors of said protocol were insufficiently diverse because they didn’t know that “AAVE” stood for African American Vernacular English in the US. Now, the thing is that the word Aave is a Finnish word that means ghost, and the authors of the protocol were Finns, and it was a great word for what the protocol actually did (namely flash loans that could disappear in a second).

So, what this actually represented was Woke American chauvinism in the name of tolerance. A citizen of this gigantic global empire, the American empire, was using woke language to assert authority over some poor Finns as insufficiently respectful of the people his fellow Americans had once oppressed. Quite a trick: America’s history of slavery used to justify America’s present of imperialism! And again, this is similar to a Soviet soldier filling the ear of an Estonian civilian with the story of how Russian capitalists had once grievously oppressed Russian workers, a problem which Comrade Lenin solved with their glorious October Revolution...and that’s why they rolled the tanks into Tallinn. A non sequitur logically, but a useful tool ideologically.

So: as communism once served the cause of Russian imperialism, wokeness now serves the cause of American empire.

But this is also its long-term undoing. Wokeness is an ideology of critique and it’s an uncomfortable fit for power. The contrast was a little too obvious when the narrative moved from tearing down George Washington to tearing up over the Capitol. It was all instrumental outrage, switched off on command as Time Magazine documented, very similar in its own way to the party-line whiplash over Molotov-Ribbentrop 80 years ago. Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia. Now that wokeness was in control of the American state, the profane was suddenly sacred. But because wokeness now formally controls all national American institutions, it owns everything the US state does at the federal level — and much of what it does is (a) incompetent and (b) indefensible, at home and especially abroad. Especially the money printing, which may lead to a surprisingly rapid denouement over the next decade or so.

But the question then is what has the strength to stand against wokeness, what has the strength to to build these parallel institutions that are to Woke America what the US was to Soviet Russia? Here I think that some combination of (a) internal US doggedness (at the state and local level, because many Americans — Democrat and Republican alike — still aren’t woke) plus (b) liberals in the broad sense abroad plus (c) Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies may eventually be a winning global coalition. Crypto as the new nonviolent NATO, the tool for defense of free societies everywhere. Because wokes believe there are no limits to money printing, so they’ll spend down their patrimony, and thus a broadly liberal and internationalist coalition that can outlast the collapse of the dollar has a chance.

Now, I know that’s a huge thing to just put into a casual statement like that, but it’d really take me many more pages to outline it all, and I’m trying to save some for the book. There’s more, including the whole foreign policy aspect, which includes both how bad China is getting and how incoherent it is to try to “check the rise of China” whilst also “checking one’s privilege”. However, see this podcast (Woke Capital, Communist Capital, Crypto Capital) and this article (Bitcoin is Civilization) for more detail.

The next four questions are ones I believe far outstrip any others in importance, and no mind on earth is better equipped to find answers. The first question is:

Since every person I’ve ever met has been sick in some way or other (with a third of Americans reporting frequent experience of pain in a 2017 survey conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research), health is an area which seems to have the most potential for maximizing human good. But innovations like cas9 and even the more recent mRNA vaccine advances (with nations with the highest vaccine compliance having roughly similar COVID case counts as nations that are least compliant), despite giving some glimmer that major inroads against illness are being made, have failed to deliver any major gains to health, which seems to be the case for the bulk of new medical technologies developed since the discovery of antibiotics like penicillin. Health economist Robin Hanson has found that increases in medical spending (which includes research and development and has now reached into the hundreds of billions in the US alone) have shown no effect on population health over time, especially relative to non-pharmaceutical interventions like exercise and campaigns to dissuade smoking: Is health an area best left to solutions outside technology?

I’ve been digressive here, but will do lightning round for this and all remaining questions.

I think the short answer on this one is that the blocker isn’t really technology per se. There’s plenty of amazing biomedical tech in the pipeline that can’t make it to the customer. Much of that is due to the US medical system, where you have third party payment, fourth party pricing, and fifth party regulation. I’m referring to the US employee insurance model (as opoosed to a Singapore-style HSA model), the AMA’s price fixing via CPT codes, and of course the web of biomedical regulations centered around the FDA.

To unlock biomedical innovation we need to figure out what is to the FDA as Bitcoin is to the Fed and Ethereum is to Wall Street. What technology, or tactic, or combination thereof will get us a special economic zone for biomedicine — a special innovation zone if you will? In many ways that’s what crypto is, or was — through decentralization, we could achieve a relatively free zone in the cloud without the same restrictions as on the earth.

A few quick ideas on how to do this.

Your body, your choice. If you can legally skydive or bungee jump, if you can serve in the military and risk life and limb, you should be able to take arbitrary risks with your own health. That means expanded right to try and new pathways outside the FDA, both at home and abroad. See this tweet.

Shadow review agency. The FDA is not a consumer-facing entity. Its reviews of drugs and devices are not built to be understood by the people who are actually using drugs and devices. That’s why you often get a wadded up chemistry textbook with your vial of drugs — the package insert interface isn’t built for the masses! But if we think of regulation as information, there’s room for doing a better job on so-called “Phase IV” reviews (postmarket surveillance) outside the FDA. Basically, start by reviewing already approved drugs [and devices] in an easy-to-understand but also technically rigorous way. Accompany this with open source technical critiques and commentary on FDA decision-making on Phases I-III. And then, as you build the following, eventually start partnering with national governments abroad and state governments at home to become an officially recognized alternative to the FDA review process.

Third party reviewers already exist of course. But the key with all this is to create a shadow alternative agency (similar to the UK concept of a shadow government) which is both fully technically rigorous for the curious scientist and fully understandable to the general public, yet which lacks any ability to coerce, and which needs to operate on a shoestring relative to the legacy institution. Seems difficult! But then Bitcoin was developed on less than one-millionth the budget of the Federal Reserve — and it’s not that hard to improve on the status quo for postmarket review with modern technology if you focus on a specific biomedical vertical.

Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom and his peers have found that, despite significant strides in research efforts, the productive output of scientific research has fallen steeply over time, which he chalks up to good ideas simply being harder to find. Does human discovery have the same constraints as those that govern physical systems? Is innovation becoming a pure physics problem?

This is a long answer that could merit another whole essay. But the short version is that I think the US research establishment set up by Vannevar Bush in the postwar era is now past its prime. It’s an academic jobs program, as exemplified by the ubiquity of things like the h-index, which has the value "h" if you have at least h papers with h citations each. Every academic is optimizing their number of citations in high impact journals…but what actually matters for science is not number of citations but independent replication.

And where are the metrics for independent replication? Where are the incentives for that? Not in academic science, where replicating a result isn’t considered novel or publishable or grantworthy. Indeed, replicating a result is often considered hostile. And that’s why we have the academic replication crisis.

An alternative model to this is something more like what’s been bubbling in open source and crypto over the last few decades. Basically, the reproducibility of open source is built in — it comes from the fact that you can just download and run it. And if you can’t, it’s not going to be imported into someone’s program, let alone compiled or built. Just the ability to reproduce the result on your computer is a much higher bar than simply citing someone without trying their code.

Reproducibility is just one piece of the puzzle, but I made some remarks on how we can take this line of thinking quite far in a recent talk on rebuilding our information supply chain.

Going off the beaten path of questions on innovation for a moment: Innovation as I understand it now, with the internet eating the world, demands that we become something a little more than human as time goes on and as our devices become increasingly integrated into our lives and biology, and this is always seen as a good and consequence-free thing. But one glaring hurdle to achieving the future we imagine, our cars being gadgets, our houses, clothing, and eventually our brains being gadgets too, is that this would mean unprecedented exposure to non-ionizing radiation, a nontrivial cause of cancer and other severe illness, which freaks me out every time that I even consider it, and makes me wonder if, in short order, the entire technology industry will shit the bed and cease in the direction it’s been traveling after a certain threshold of exposure becomes intolerable to the public and attributable to enough instances of childhood leukemia and the like. Such burdens on our systems adding markedly to cancer risk make technology seem inherently self-limiting, like a drug too mind-expanding for most people to enjoy after a long time, and with the International Agency for Research on Cancer deeming EMFs carcinogenic to humans, I want to ask: Do the benefits of innovation outweigh the risks of radiation exposure, and can the radiation problem be circumvented?

Interesting question. My immediate reaction is that with better quantified self we’ll have empirical long-term measurements on people’s health, so we won’t need lots of contradictory studies to puzzle this one out. There’s probably individual variation in the response to this, for example, as there is with everything else (eg some people metabolize caffeine better than others).

There’s a lot of safety testing that most gadgets in our home have been put through (see the FCC insert in most devices), but you’re right that we’ve never been exposed to as many electronic devices as constantly as we have over the last few decades. Similarly for artificial foods, and plastics, and various kinds of chemicals.

I suppose my answer to this is: we’ll get better metrics, long term metrics, via quantified self. And then we’ll see if we are really doing the equivalent of drinking from lead pipes (like the Romans did) or licking radium watches (like some Americans did). But then the answer will be to make the analog of non-lead pipes and non-radium watches — not to give up on running water and timekeeping and technology.

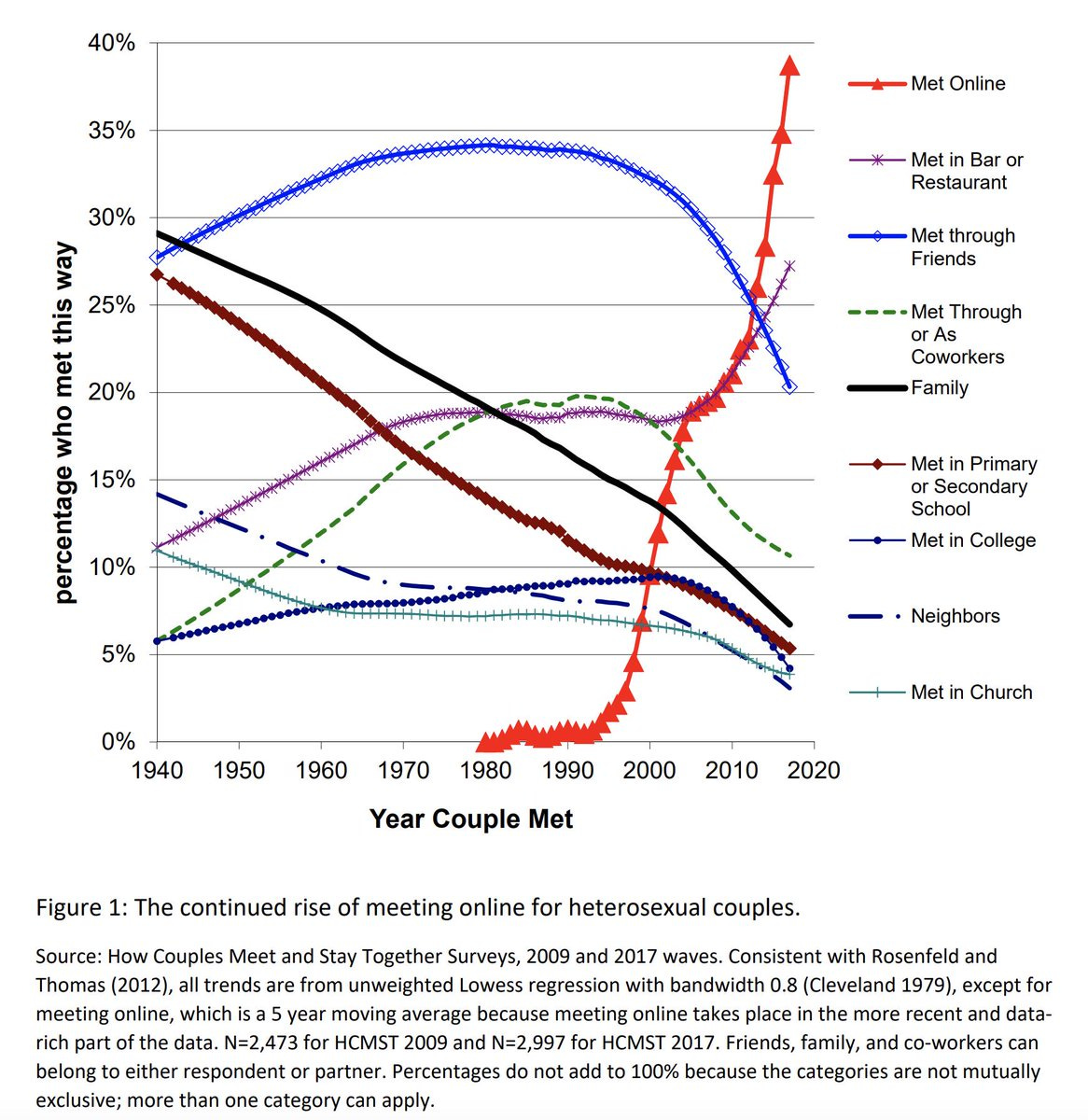

The final question I have for you is: Nearly half of all relationships now begin online at a time when the birth-rate in the United States has fallen to its lowest level in history across all racial demographics, and with 50% of singles reporting no interest in relationships in a 2020 Pew Research survey and nearly half of adults reporting feeling lonely, the rise of online contact and the widespread flagging of human intimacy may bear some relation. Additionally with 40% of men reporting that they had ten or more friends in 1990 but only 15% having the same now in a study conducted by the Survey Center on American Life (and nearly 30% of women reporting ten or more friends in the same timeframe with only 11% reporting ten or more now), something strange seems to be happening in the realm of basic human interaction. It’s hard to describe and its etiology may be even more elusive, but it feels weird as hell, atomizing and avoidant. It may be due to the window-shopping quality of being online, with a few studies finding a link between online dating and choice-overload and subjects eventually choosing nothing and no one at all, or maybe our reward systems are simply being trained toward the low-hanging fruit of scrolling instead of the more challenging task of getting to know someone, since both may engender equal levels of gratification at disparate cost. It almost seems pointless to reach out to anyone now, which is sad since I want to make more friends, share the world inside the heads of others and share a world of my own, but it seems few are friends to anyone anymore, so I have to ask: How do we migrate the physical world to our devices without killing our raison d'être, love and friendship?

Another excellent question which could merit an essay length response. But let’s start with data, specifically this graph:

As you imply, that’s an epochal change in human history. There are few things humans have been more interested in than other people’s mating habits, whether that’s Pride and Prejudice or various religious injunctions on family and marriage. And now that’s all gone away and replaced with straight peer-to-peer matching via the internet. The village that used to evaluate a suitor is now completely gone.

There are signs that community-based matching may be making a comeback though. The shoot-your-shot thing on Clubhouse, for example, is this really interesting phenomenon where a whole group of people judge the suitability of a suitor in public and realtime. Another example is this (comical) interaction between my friend Nic Carter and Twitter personality Jessica Vaugn. Of course, the whole thread is in jest, but it gives new meaning to the term “social proof” when your social media like count is used to establish your viability as a suitor. It also gives an opt-in public announcement that these two people may be seeing each other; this can be desirable under some conditions.

So my short thesis on this one is — as with everything, the internet is unbundling and then re-bundling. We unbundled songs from CDs and rebundled on playlists. We unbundled articles from newspapers and rebundled them on social feeds. And now like it or not we’re doing that to core societal institutions like dating and marriage. We basically just unbundled all pair mating relationships from every legacy pre-internet societal structure. Now we may be in the process of rebundling into internet communities that facilitate lasting pair bonds which benefit all parties. Let’s hope so, let’s make it so.

Follow Balaji Srinivasan on twitter to stay a few thousand years ahead of the future and subscribe to his brilliant new project at 1729.com for more!