Editor’s note: Ives Parr and I have been going back and forth about the value of formal schooling over text lately, and decided it would be fun to bring our debate into the blogosphere! I hope you enjoy his provocative insights as much as I did.

Make sure to check out his newsletter on the intersection of genetics, philosophy, and culture and let us know in the comments where you agree or disagree as I will be writing my response to Parr next week. -Infovores

I. Ethical Double Standards

In the United States, there is a widely held belief that people should face equal legal treatment regardless of race, sex, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation. This is especially the case among contemporary progressives, who have made it their raison d'être to eliminate the social and political inequalities experienced by marginalized groups. Despite the ever-growing concern for discrimination along different dimensions of personal identity, many do not recognize that they have inconsistent attitudes about the treatment of the young.

Most would rightfully abhor restricting women’s ability to pursue a career merely because she is female. Also, abhorrent would be coercing minority races into narrow career pathways, even if it was supposedly for their benefit. However, many find it not only acceptable but morally obligatory to restrict children’s ability to work. Moreover, they advocate for universal compulsory schooling regardless of individual students' circumstances and psychological characteristics.

Perhaps this incongruity in progressive thinking is downstream of the egalitarian fallacy, wherein people’s moral commitment to equal treatment leads them to believe that people possess equal amounts of the traits that give them moral standing. Since children and adolescents lack various qualities that give them equal moral standing, they should be treated differently. For example, children and adolescents have lower average cognitive ability and practical knowledge. While this is undoubtedly true on average, there are overlapping distributions. Moreover, hardly any progressive would be consistent in advocating the restriction of the rights of an ethnic group provided they had a lower average level of cognitive ability.

While some minors may be more intelligent than the average adult, they have yet to complete their education. Maybe the transformative effects of education are so powerful that they warrant restricting the uneducated young from the rights adults enjoy, such as drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, undergoing surgery, living alone, signing contracts, getting credit cards, gambling, and working a job. Maybe the benefits of education are so powerful that they warrant punishing truant children and their parents. But if the benefits of education are so incredible, why not have mandatory adult education?

Most people accept that coercion is morally appropriate in some circumstances. For example, preventing adults from abusing fentanyl is regarded as acceptable. In contrast, it is not considered moral to coerce a non-criminal adult into education regardless of how uneducated, unintelligent, unknowledgeable, or unwise they are. But it is widely accepted that it is morally obligatory to coerce children and adolescents into schooling irrespective of how educated, intelligent, knowledgeable, and wise they are.

While it is reasonable and necessary not to treat the young like adults in many circumstances, such wildly differing standards don’t seem wholly justified. I don’t want readers to lower their standards and embrace compulsory education for adults. Instead, I want readers to consider having a higher standard for what warrants coercion against the young. I also would like readers who despise discrimination in other contexts to refrain from using some members' traits as a strong justification for reducing the rights of all group members.

It could be that even with higher standards to warrant coercion, compulsory education still wins out as a worthwhile endeavor. Still, if many of the significant benefits are critically undermined by empirical data, one ought to advocate for less education in some form or another. While it could be the case that a hypothetical curriculum could pass a cost-benefit analysis, I will judge the education system as it currently stands. I agree with Bryan Caplan’s stance in The Case Against Education that we should stop wasting time and money until this worthwhile curriculum is discovered. If you are taking medicine that does more harm than good, stop taking that medicine until you find one that works.

II. Empirical Double Standards

When looking at complicated systems like societies, you will find many cases in which good things go together. Everything is correlated. Some zip codes have low crime, high educational attainment, high average income, better than average health, and more beautiful homes. Wealthy people tend to be more intelligent and maintain two-parent households. These parents also tend to have more intelligent children who do well in school and go on to have successful and high-paying jobs.

One possible explanation for this relationship is that people attain high socioeconomic status and pass it on to children directly and through better schooling. In this view, schooling enhances the child’s cognitive ability and provides them with the knowledge that further benefits them in their career and life. While conservatives emphasize the importance of a two-parent household, progressives tend to highlight the need for better and more equitable schooling. Both agree that education is essential, but conservatives often believe school choice is the way to improve schooling, while progressives typically believe that funding education is the best approach.

I have an alternative view. The typical progressive and conservative causal explanations are overstated. Most of the variance in education and significant life outcomes in the developed world is due to genetic differences or idiosyncratic environmental influence. Education does not work as intended. Attaining genuine equality of educational outcomes is not feasible. This viewpoint receives little mainstream attention because it is somewhat pessimistic, stigmatized, and counterintuitive. While some people do not want to accept the implication that we waste billions of students’ hours and trillions of dollars, many are just not exposed to this view. I learned this perspective from Bryan Caplan, who is responsible for much of my thinking on education.

Advocates of socially undesirable views are unjustly held to a higher level of scrutiny, so it is challenging to do away with this widely held belief. Those who advocate continuing to spend exorbitant amounts of time and money on a program should establish beyond a reasonable doubt that it is working. Since markets tend to weed out costly and unworthwhile endeavors, I believe the current education system survives through coercion and subsidy.

One aspect of some discussions about education is that if key arguments are undermined by empirical evidence, arguments about difficult-to-measure benefits are proposed. I think it is reasonable to be skeptical of practices that become established as commonplace and then retrospectively justified with different arguments. If one is not beholden to the status quo, refuting primary justifications should temper enthusiasm for schooling rather than result in support for the same amount of education justified by other arguments.

III. Mostly Useless and Irrelevant

The need for memorization of historical facts, spelling rules, multiplication tables, arithmetic operations such as long division, basic scientific facts, and a whole host of other pieces of information is seriously undermined by the widespread ownership of smartphones among young adults. A Pew Research poll found that 96% of US adults aged 18-29 had access to a smartphone. Almost all smartphones have the capability to quickly and accurately make calculations or search the web for information. It is better and faster than having an encyclopedia, calculator, and dictionary in your pocket.

Consider how often the average adult finds it necessary to relearn topics such as long division, multiplication of large numbers, or the periodic table of elements. That information is either largely unessential or so quickly accessed with the help of the internet that it is not worth memorizing. There is always some possible justification for every tidbit of information, but we must scrutinize the utility of this data from a cost-benefit perspective. Caplan properly analogized these sorts of arguments to hoarders who overflow their homes with things on the off-chance that they may need them someday.

Despite their ability, adults hardly ever need to use their smartphones to recall information they learned in school because it is hardly ever relevant. These facts are unessential for a successful career or life. If everyone had a closet filled with every textbook from kindergarten to undergraduate, I would guess these books would go almost entirely untouched. Suppose someone does want to consume information about science or history. In that case, it is because of an inherent interest in the topic rather than suspecting that it is necessary to their everyday life. They will likely pick a more engaging form of media like television, movie, documentary, podcast, or audiobook.

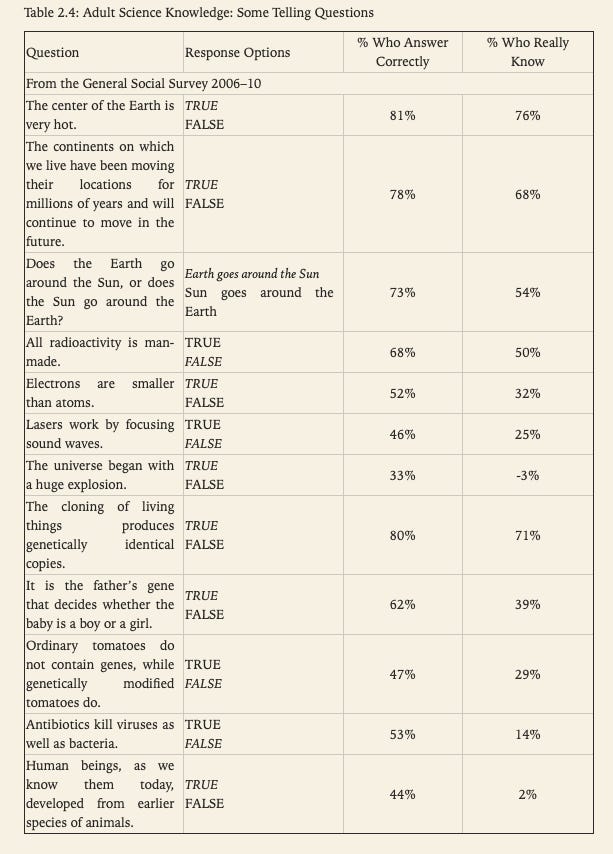

Even if a piece of information was necessary for an adult to know and there was a solid reason why they could not merely look it up with their phone or computer, future students may have forgotten it. We should not give education credit for more than it has accomplished. Bryan Caplan discusses a fair amount of polling of adult knowledge in his book The Case Against Education. He found that many adults polled in the General Social Survey were ignorant of fundamental scientific facts. Consider that familiarity cannot be entirely due to education since other sources could teach or reinforce this information.

We would expect that more advanced questions would receive lower scores on average. The problem of information retention is well demonstrated by foreign language acquisition. Few graduates exercise their foreign language skills after they are no longer in school. This information is not likely to be reinforced to any substantial degree in the United States due to the dominance of English. We would expect low retention levels, and that is what we find. Caplan writes:

High school graduates average two years of foreign language coursework. What do adults have to show for it? The General Social Survey allows rather precise estimates. It asks respondents, “Can you speak a language other than English?,” “How well do you speak that language?,” and “Is that a language you first learned as a child at home, in school, or is it one that you learned elsewhere?”

The results could scarcely be worse. Schools make virtually no one fluent in a foreign language […] Only .7% claim to have learned a foreign language “very well” in school; another 1.7% claim to have learned a foreign language “well” in school. Since these are self-reports, true linguistic competence must be even worse. The hard truth: if you didn’t acquire fluency in the home, you almost certainly don’t have it.

Many people who have used spaced repetition software like Anki have become familiar with the time cost of memorization. Certain information is not worth learning, even using the most efficient methods. Forcing recall of the information makes the forgetting process more salient. When regular users do not use their spaced repetition software for an extended period of time, they often struggle to get back on track as the cards due are overflowing and recall is especially difficult.

Most students do not need to use spaced repetition because the education system incentivizes students to cram and forget. Few care to try to retain facts about academic subjects outside of school. This is rational from their perspective. I spend a lot of time reading books, articles, and papers, yet I still think learning is overrated.

I would not be surprised if someone could provide cases in which the information they learned was both remembered and relevant. These bits of information must be considered in the full context of the thousands of hours dedicated to other bits of information which were forgotten or irrelevant. Those who learn about a scientific field during their schooling and eventually have professions in that field are unusual, although overrepresented among readers of blogs such as this one. Exposing children to topics by allowing them more choice in what they learn about would be significantly more pleasant than the current system and perhaps better inculcate an appreciation for academic issues.

To be clear, I am not advocating for the children who love learning to be prevented from doing so. We should give brilliant students with scientific fascinations more time to pursue those interests. And for those who enjoy more practical tasks, we should be more willing to encourage vocational training. Every child is different. I don’t want to ban education. I want drastically higher standards for what is considered so worthwhile as to justify forcing it upon a person, even if that person is young.

IV. Learning How To Learn

Education could perhaps be redeemed if it enhanced ones thinking ability and improved one’s ability to learn. IQ best measures this. Although it is controversial in the sense of being taboo, it is a well-replicated scientific finding that a wide range of test items of cognitively demanding tests positively correlate. This gives rise to the statistical construct known as the g factor. It is called the g factor because it is considered to be general intelligence. Anything that people do that requires thinking relies to some extent on the g factor.

Scores on cognitive ability tests are expressed as relative measures, typically presented with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 points. IQ is a score. General cognitive ability is an aspect of a person’s mind or brain. The g factor is a latent variable that is unobserved directly.

By imperfect analogy, imagine you wanted to be fluent in Spanish and measured Spanish fluency with a written test at a testing center. The first time you took the test, you scored very poorly. If I were to present you with a sheet of some of the test answers I had stolen from the testing center, would you be interested? You would not because you want actual fluency rather than a high test score. Similarly, we want real gains in general cognitive ability rather than mere increases in test scores.

Unfortunately, it appears that education is increasing IQ but not increasing general cognitive ability (Lasker & Kirkegaard, 2022; Hu, 2022; Kirkegaard, 2022). This is reflected in the fact that not all g-loaded test items see improvement. It is as if you purchased my cheat sheet and became good at the test but noticeably saw no improvement on certain items, namely the ones not on the cheat sheet. If you were truly fluent in Spanish, it would be odd if you became exceptionally good at certain test items but never got any better at others. This would matter because you want to be able to have a conversation in Spanish, not complete a test.

Similarly, we want people to have higher IQs because general cognitive ability comes with many good things. We want the good things, so we want improvement in general cognitive ability. We do not just want improvement on test items because these improvements wouldn’t transfer to all the various real-life cognitive skills.

Not only does training in some skills not improve general cognitive ability, it seems that it only improves the narrow skill you are focusing on and skills very similar to it. It would be nice if learning irrelevant skills mattered because it had benefits in career-related skills. For example, reading Shakespeare makes you better at certain critical thinking tasks. This is unlikely to be the case to any large extent. From my review of Cracks in the Ivory Tower:

Some argue that rather than giving students knowledge about liberal arts specifically, teaching students in humanities teaches students how to think. It develops critical thinking skills generally through a process called transfer of learning. Caplan explains that over a century of study has gone into transfer of learning and psychologists’ chief discovery has been “Education is narrow. As a rule, students only learn the material you specifically teach them ...if you’re lucky” (Caplan, 2018, p. 50). Furthermore, according to psychologist Robert Haskell:

Despite the importance of transfer of learning, research findings over the past nine decades clearly show that as individuals, and as educational institutions, we have failed to achieve transfer of learning on any significant level (Haskell, 2001, xiii).

According to psychologist Douglas Detterman:

Transfer has been studied since the turn of the [twentieth] century. Still, there is very little empirical evidence showing meaningful transfer to occur and much less evidence for showing it under experimental control (Deterrman, 1993, p. 21).

Terry Hyland and Steve Johnson believe:

On the basis of the available evidence, however, drawn from many very different disciplines, we believe that the pursuit of [general transferable] skills is a chimera- hunt, an expensive and disastrous exercise in futility (Hyland and Johnson, 2006).

It appears that the claims made by many universities in their advertising are false or misleading. At the bare minimum, it would appear there is insufficient support for the empirical claims that are made. Universities have not done their due diligence to verify the veracity of their claims, but they continue to profit from misleading advertisements.

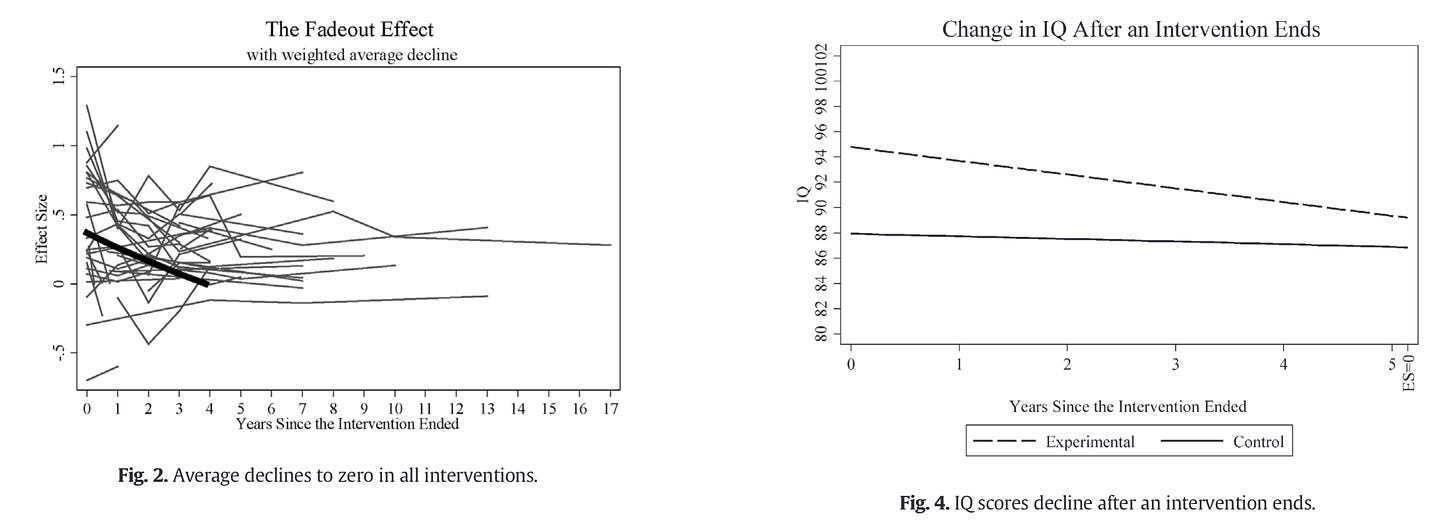

Unfortunately, even if we granted the best-case scenario that the gains from education were of general cognitive ability, there is a widespread phenomenon known as fadeout. Gains in IQ do occur, but they tend to disappear with the passage of time. Protzko (2015) analyzed 7584 participants across 39 randomized controlled trials finding “after an intervention raises intelligence the effects fade away…because children in the experimental group lose their IQ advantage and not because those in the control groups catch up.” This means that those who get treatment and those who do not get treatment end up with the same IQ after several years. If an intervention occurs early in life and there are no noticeable benefits once a student goes into the real world, it is hard to justify the intervention in the first place.

This should not be particularly surprising. Skills fade. People forget things. If one does not make permanent dietary changes, gains from dieting do not last forever. If someone has a depressive episode, they often feel better with the passage of time. Regression to the mean is ubiquitous. If IQ interventions worked, persisted, and were permanent, some people could study for decades until they achieved superhuman intelligence unless there were diminishing returns of some kind. Interventions like preventing iodine deficiency in pregnant women likely work because they change how the actual brain forms. Traumatic brain injury diminishes IQ, probably because it causes physical damage to the brain. Other interventions likely fail because the brain is plastic and inserting information into the brain rarely creates connections that persist for long periods of time without reinforcement.

V. Studies on Education Interventions

Since the natural human tendency is to disregard information contrary to one’s worldview, we ought to take notice when we see a growing begrudging acknowledgment of reality. The quotations about the transfer of learning research reflect that social scientists want to find transfer of learning, yet they still do not. There are so many studies about the cognitive benefits of education because people want to find results. Despite this overwhelming bias in favor of successful interventions, the evidence continues accumulating, pointing toward failure. Various people of differing beliefs have recognized education’s failure to get desired returns.

Notably, libertarian economist Bryan Caplan is highly skeptical of education’s effectiveness. On the other end of the political spectrum, Marxist Freddie deBoer describes the failure of education to create equal outcomes in his book The Cult of Smart. He also wrote at length about this in his provocatively titled “Education Doesn’t Work.” According to deBoer, students sort themselves into ability bands early in life and do not vary from them. Genetic differences drive differences between students’ academic abilities. DeBoer takes a far-left perspective, viewing the inequality generated from genetic differences as unjust.

On the other side of the political spectrum, researcher Emil Kirkegaard believes that “Education interventions keep not working.” In his review of several meta-analyses of education interventions, Kirkegaard concludes, “[t]his sets a very strong near null prior on such interventions.” He also notes that even the left think tank Brooking Institute finds pre-kindergarten interventions don’t work. Brookings expert Grover Whitehurst says in his report "Does state pre-K improve children’s achievement?” that:

Under the most favorable scenario for state pre-K that can be constructed from these data, increasing pre-K enrollment by 10 percent would raise a state’s adjusted NAEP scores by a little less than one point five years later and have no influence on the unadjusted NAEP scores.

Unabashed enthusiasts for increased investments in state pre-K need to confront the evidence that it does not enhance student achievement meaningfully, if at all. It may, of course, have positive impacts on other outcomes, although these have not yet been demonstrated. It is time for policymakers and advocates to consider and test potentially more powerful forms of investment in better futures for children.

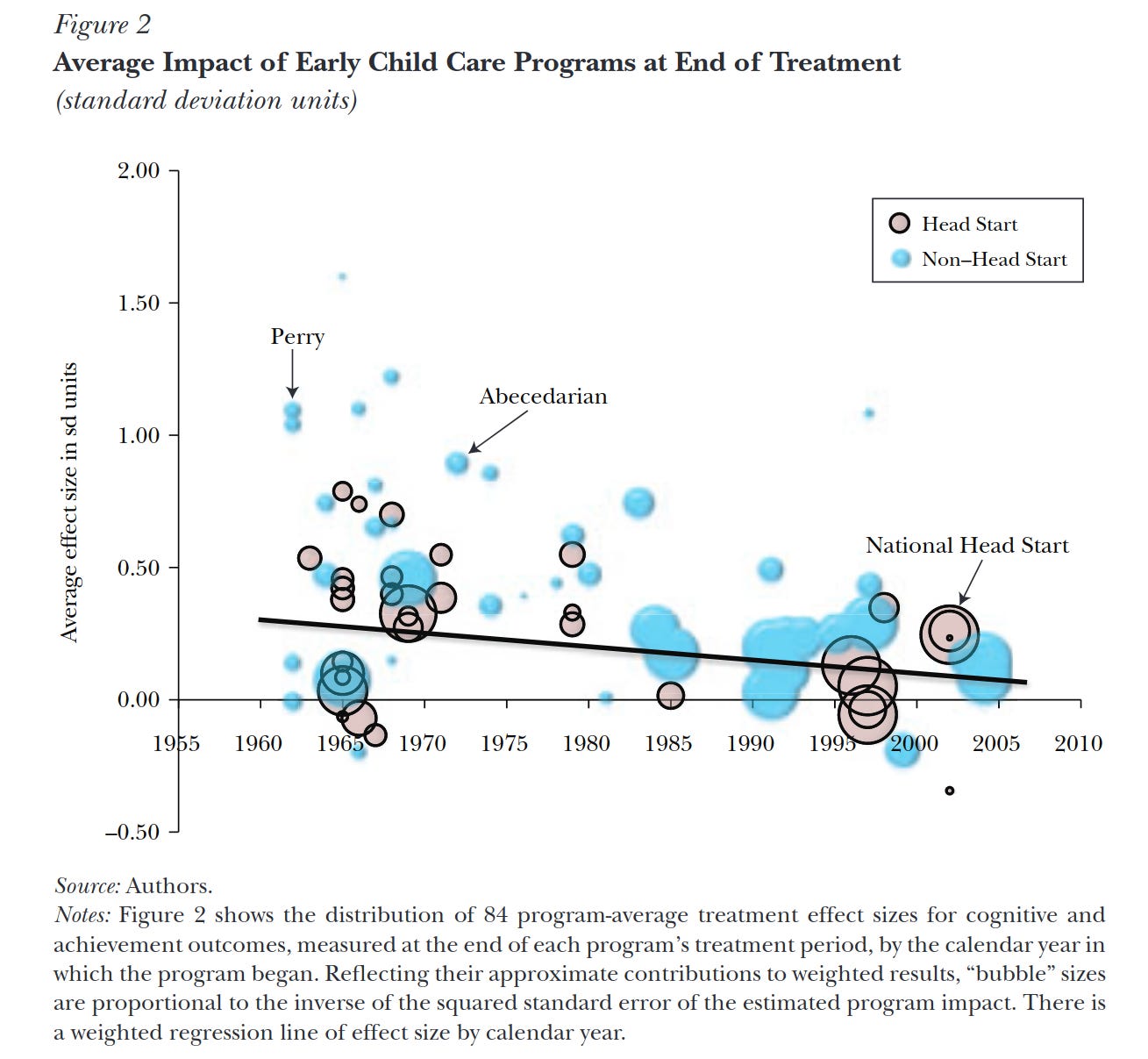

If one is a proponent of the Heckman Curve—the idea that earlier interventions have a larger impact, then this casts doubt on the success of later interventions as well. The economist James Heckman, after which the curve is named, has spent much of his career studying early childhood interventions, especially the Perry Preschool Project. Both Kirkegaard and DeBoer included a chart in their articles from Duncan and Magnuson (2013) showing a decline in the effectiveness of education interventions across time, with the Perry Preschool project as an outlier program with an impressive effect size:

The most likely explanation for the decline in efficacy is that studies are better designed and have more participants. The increased bubble size indicates a larger inverse of the squared standard error. If you have a small standard error, the inverse of the square will be large. A small standard error means that your effect size estimator has a tighter distribution. All things equal, it is better for a study to have a large bubble. As the bubbles get larger, we should expect convergence on the true estimate. In this case, it appears to be around zero.

The Perry Preschool Project is an unusual outlier regarding early childhood interventions. It is not all that unusual to have some studies outside the norm for whatever reason. This could be because of their extreme nature. For example, in the Perry Preschool Project, “The participants of the project were provided a stimulating classroom education, as well as weekly home visits that were meant to teach mothers how to best support their child’s development by extending the preschool curriculum into the home.” Implementing this on a large scale may be unfeasible, and it may not be a good idea to think this means that regular preschools will have similar results.

How much should we weigh outliers? Perhaps not all that much, especially when they are rather atypical forms of intervention. It is possible that outliers are a consequence of poorly designed studies, although I cannot speak to this outlier in particular. Research goes wrong for a whole lot of reasons. If a study is outside the norm, we have some reason to expect a problem. With the Perry Preschool Project, it appears we’ve reached a rather absurd amount of analysis. In Alex Tabarrok’s review of The Parent Trap, he humorously remarks:

At this point in the book, it was almost inevitable that we were going to get yet another paean to the Perry Preschool Project and indeed Hilger waxes enthusiastically about Perry. Seriously? The Perry Preschool project started in the 1960s and had just 123 participants (58 in treatment and 65 in control!). There are more papers about the Perry Preschool project than there were participants. I am jaded.

It is possible that people will object to my argument by noting a successful intervention program somewhere and at some time. I would argue that we ought to beware of weighing individual studies too highly. The correct approach is to look at meta-analyses, investigate publication bias, and consider various lines of evidence.

In Kirkegaard’s review, he also cites a meta-analysis of studies on education in the UK and the US entitled “Rigorous Large-Scale Educational RCTs Are Often Uninformative: Should We Be Concerned?” They found a mean effect size of 0.06 standard deviations and a mean width of the confidence interval of 0.30 standard deviations. This effect size should not inspire optimism.

Once again, a better-designed and more powerful study will give a smaller standard error. The inverse of the standard error will be larger. The idea behind the plot on the right is that the higher the inverse of the standard error, the more accurate you would expect the effect size estimate to be. One of the issues with meta-analysis is that you could have systemic biases across studies which give rise to a systemic bias when aggregated. This bias likely favors the pro-interventionist side. The skew on the right-hand side indicates publication bias in favor of successful interventions. If both types of studies had an equal chance of being published, we would expect a symmetrical distribution. For this reason, it would be reasonable to suspect that the 0.06 standard deviation effect size is an overestimate, dragged rightward by publication bias.

VI. What Explains Employers’ Desire for College Graduates?

I’ve argued that education is largely irrelevant and that education does not make you smarter in the way we would like. I’ve also made the case that students forget the content they learn anyway. This should be mysterious. Why would employers value high-school and college diplomas for their workers? Why does a college degree improve lifetime earnings by so much?

One partial explanation is that people who attend college earn more because they are higher in the skills employers desire, an effect called ability bias. These are people who go to college but happen to be more gifted in income-earning skills. Another explanation is that some aspects of schooling are useful. This is called the human capital view. Proponents of the human capital view believe that education improves your ability to be a productive worker. I do not dispute this, especially for certain disciplines in college. I just think the benefit of this aspect of education is vastly overestimated.

Finally, one possible explanation is that education is largely signaling. School is used to differentiate between students because some lack the willingness or traits that make them successful at school. In this view, education serves as a filtering mechanism. Students go to college because it lets them demonstrate their positive qualities.

Bryan Caplan defends the view that the true college wage premium averages approximately 80% signaling and 20% human capital. One strong piece of evidence for this estimate is the sheepskin effect, the fact that there is a sizeable discontinuity between those who gain most of the skills by almost finishing college and those who actually earn a diploma. With such a high signaling estimate, we have a plausible explanation as to how irrelevancy and fadeout could be so widespread and yet education so lucrative.

Caplan believes that employers care about intelligence, conscientiousness, and conformity. Students who are extremely intelligent and try to bypass schooling by demonstrating their cognitive ability through testing will appear unconscientious. Wanting to skip school looks lazy. Students could try to demonstrate their intelligence and conscientiousness through some intellectual accomplishment, like publishing a book, but they will appear rather non-conformist. The conformity aspect makes breaking the societal norm send a bad signal. Many are stuck in this game in which it is individually advantageous to go to school but collectively highly wasteful.

Estimating the returns to elementary through early high school would be difficult, seeing as it is compulsory. I would suspect that if it were voluntary, it would also be mainly signaling. Students spend a lot of time on things that do not appear to increase human capital, like coloring, playing the recorder, gym class, music class, and so forth. I would suspect that students don’t need these things. Caplan supports the view that there are overestimates of human capital attainment in elementary school and that people do not recall all the silly time-wasting activities they did while students.

Students may not even need early mathematics or reading, seeing as missing skill is not a significant issue in many cases (Alexander, 2021). The ability of students to catch up after missing school calls into question the harms of missing school. Although I do not have strong evidence, I suspect that teaching students mathematics and science at an early age is unnecessarily difficult because they have extraordinarily low cognitive ability due to their undeveloped brains. I think merely waiting until after puberty would make learning the same information much simpler.

VII. What Is To Be Done?

If you still believe in the overwhelming benefit of education, perhaps you should consider advocating for compulsory adult education, especially for the less well-educated adult population. However, if I have persuaded you that education is mostly irrelevant, forgotten, and unable to improve thinking skills, then you ought to advocate for at least some changes to the status quo. Since the amount of schooling necessary is drastically less than what passes cost-benefit analysis, we ought to support significant reductions in school time. I would advocate for the following policies:

More recess: Children enjoy recess.It provides an opportunity to play with their friends. If one wants education for reasons of socialization, this seems like a great and natural way of socializing.

Less homework: Homework is harmful for the same reasons as schooling, namely irrelevancy and the problem of forgetting. Research does not point conclusively to homework working well anyway (Alexander, 2022). It is even worse because it interferes with children’s time to relax and play. Since education is largely zero-sum signaling, high school students who want to attend a good college must compete with each other in the “rat race.” If little is gained from homework, this is a disturbing state of affairs considering how many anxious and overworked teenagers there are.

Shorter school day: School days should be cut drastically. If parents need babysitting, let students play games together or hang out and pursue their interests under adult supervision.

Teach civic knowledge closer to when needed: If it is essential that students be future-informed voters and educating adults is not possible, then it would be better to cram material relevant to voters in students’ final years. Even better would be just mailing relevant information to potential voters and then testing them over it at the time of registration.

Teach technical skills that are immediately useful: Teaching students career-relevant information like mechanics, nursing, plumbing, electrical work, and construction while they are still in high school would be very beneficial. The skills would be better retained if students immediately went into those fields.

Child labor: If one believes that discipline and socialization are essential, one might be sympathetic to more child labor. School is a social environment unlike any other, and working at a job would teach discipline and what it is like to work. Students who work could have their wages subsidized with the money that would’ve gone to educating them, typically more than $10,000 per student in the United States.

Unschooling: Allow more freedom for students to pursue their academic interests with less guidance.

My final proposal will likely be controversial, perhaps even more than child labor. I am a strong advocate for genetic cognitive enhancement. Due to recent technological advances, growing scientific knowledge, and the falling cost of DNA sequencing, it is now possible to determine polygenic scores for embryos during in vitro fertilization. When couples have to decide which embryo to implant inside of the mother, they want to select one they expect to have a successful pregnancy and live a healthy life.

Intelligence is a polygenic trait. While few companies can select embryos based on this trait, I anticipate rapid growth in this market in the near future. Many parents spend exorbitant amounts of money sending their children to private schools, getting them tutors, and taking necessary steps to ensure their child has an elite education. When polygenic screening for cognitive ability is widespread, many parents will jump at the opportunity.

Currently, polygenic screening for cognitive ability has limited utility (Karavani et al., 2019). The returns to selection for IQ are bottlenecked by the embryo batch size and our familiarity with the genetic structure of cognitive ability. Understanding the genetics of IQ is made especially difficult by ideologically motivated gatekeepers of data (Lee, 2022). To understand intelligence, we need large sample sizes, perhaps around one million for certain models (Hsu, 2014). Attaining this data would be possible with a small fraction of the money dedicated to ineffective education.

The breakthrough technology that will rapidly increase the number of eggs available is a process called in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), in which eggs and sperm can be created in a laboratory. Rather than a woman having to undergo the painful process of egg extraction, she could have skin cells taken and transformed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The iPSCs would then be converted into eggs. This would allow for huge batches of embryos. The prediction market Metaculus has a median estimate of 2033 for the first human born due to this process.

In vitro gametogenesis also provides the ability to perform iterated embryo selection (IES). Bostrom and Shulman describe the process in their paper “Embryo Selection for Cognitive Enhancement: Curiosity or Game-changer?”:

Genotype and select a number of embryos that are higher in desired genetic characteristics;

Extract stem cells from those embryos and convert them to sperm and ova, maturing within 6 months or less (Sparrow, 2013);

Cross the new sperm and ova to produce embryos;

Repeat until large genetic changes have been accumulated.

Once again, returns are dependent on our understanding of the genetic architecture of intelligence and the number of embryos in each batch. Selection in moderate-sized batches could provide worthwhile and life-changing gains. Since intelligence is highly polygenic, it is possible that gains from many iterations of large batches could be so significant that this process creates people smarter than anyone who has ever existed.

Another advance in reproductive technology is gene editing. If scientists mastered gene editing with little to no errors, there could be even more gains through targeted genome edits. These reproductive technologies are not exceptionally far-off, and some have already occurred. A baby has already been born after undergoing polygenic screening—Aurea Smigrodzki. Two babies have already been born after being gene-edited with CRISPR/cas9—Lulu and Nana. Scientists have accomplished in vitro gametogenesis in mice. Genomic Prediction co-founder Steve Hsu has said, “Pretty confident in 10 years or so, the CRISPR gene editing technologies will be ready for massively multiplexed edits.” Super-intelligent humans are coming.

From a cost-benefit perspective, it is hard to imagine that this technology will not be the more worthwhile pursuit for improving human cognition. We should be pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into researching this technology. Merely biopsying a batch of embryos, sequencing their DNA, and running a computer program will provide more worthwhile information for making a child intelligent than years of schooling. While these arguments might sound very unappealing, we need to face reality. We should want to give those yet-to-be-born wonderful lives with all the benefits and intellectual richness that cognitive enhancement provides. And we owe it to today's young people to make good use of their time during childhood and adolescence. That means seriously rethinking education.

Subscribe to NeoNarrative

A New Way of Knowing

Great article

>Estimating the returns to elementary through early high school would be difficult, seeing as it is compulsory.

I estimated 97.8% of the man-hours in high school are wasted based on curriculum and occupation data.

Check out my book on this, pretty relevant to your post: https://josephbronski.substack.com/p/an-empirical-introduction-to-youth-eb9

I enjoyed this and have saved it in my homeschooling folder for further reflection on the education I wish to give my sons... Eric hoel is another writer whose thoughts I am reflecting on