Transcript edited for clarity, Spotify link here.1

Infovores 00:03

Hello and welcome to Time Well Spent, a place where the most brilliant minds in the world take on the toughest questions in science, politics, technology, and much more. My guest today is Robin Hanson—economist, futurist, and author of the influential blog Overcoming Bias, which as of this week is available on Substack. Robin, thank you for joining me!

Robin Hanson 00:24

Thanks for having me, I'm not sure we can live up to this most brilliant minds thing, but let's give it a try.

Infovores 00:29

Let’s give it our best shot.

So let’s talk about the recent developments in AI. At least in my experience, I see these sorts of things emerging as a trendy set of buzzwords getting used more and more in the last 5 to 10 years. And then it really only breaks through into the mainstream, "current thing”-level status in the last few months. But you have been researching and pondering these things much longer than most people talking about AI now. What would you most like to change about the current conversation coming from that perspective?

Robin Hanson 1:04

Well, historical perspective I guess.

So we've seen similar bursts of interest and concern about AI, going back a long way. We're now maybe near the peak of the current burst, but we had another one in say, the late 1980s/1990s. We had one in the 1960s, plausibly one in the 1930s as well although they didn't call it AI, they called it automation. And even plausibly one in the 1820s with the rise of the Industrial Revolution and concern about automation there. And we've just consistently seen over this whole time, the scenario is that some new demo and technology appears, and it starts to have impact. And then people are immediately trying to envision how far this will go, how fast, and they're saying, gee, this looks unprecedented. This could soon take over all the jobs and replace humans. And that's what people have said every time over this long period. In previous things, we've had presidential commissions and big news and media coverage about the unprecedented new abilities that have just appeared. And that's what we have again. So I'd like people to know about how that's played out each time.

Typically there are some concrete developments and some actual useful applications. And then there's more investment in terms of new firms and existing firms making new projects and students going into interrelated fields. And of course usually the fears are overblown, or the expectations are too high. And what you have is a new set of technologies that diffuses out into practice, but not a revolution. And that should be placed in the context of just say, the last seven years of computer science and computer applications, where we've had relatively steady progress. But every once in a while, we have a local breakthrough and that gets attention. But the distribution of innovation in terms of their size is almost all innovations in small things, relatively few in medium-sized things, relatively little in big things. And that's just the distribution of innovation in general, which seems to apply to most fields. But AI has this unusual potential to help people envision a much bigger impact of the thing they see in front of them. Everybody's saying that someday there's going to be machines to do everything. Could this thing I see right in front of me be the thing that I hope for or fear? And that's what's different about AI is people project these huge potential advances on the thing they see in front of them.

Infovores 04:16

Makes sense. A lot of what you're saying I think applies really to any sort of technological fad.

Robin Hanson 04:29

Well if it inspired such big visions, right? So most technological innovations don't make people think of rampaging robots. Whereas AI does and so that's the difference here. I mean, just in terms of actuality most innovation is lots of small things, and every once in a while, a big thing. But different kinds of innovations just project different images people have about what could happen.

Infovores 04:52

So the next big breakthrough in building a better mousetrap is not going to inspire the same vision because, sure it could revolutionize the field of mouse-trapping and eliminate all mice problems completely. But it's not going to threaten anybody's sense of the world being run by robots instead of humans. The interest is especially susceptible there.

Part of the motivation for asking this question was a post you wrote a few years back about how telecommuting was a really neglected trend. I think that telecommuting was kind of the last big technology breakthrough that everyone got really excited about, and now I wonder if we compare those two things side by side, are we still sleeping on remote work to some extent?

Robin Hanson 05:48

Certainly remote work has had a much bigger impact on society in the last 10 years than AI has. That’s hands-down true. But I think I still think we haven't realized most of the potential of remote work. It's still mostly there to be realized. So I think over the next 30 years, we will see it realized, but so far, we have just seen the simple thing of people working from home instead of the office, without that much changing how things are done.

Infovores 06:21

We haven’t restructured institutions.

Robin Hanson 06:23

There's a famous story about electrification, which was that originally, people had factories with non-electric power, and then they had electricity but they basically plugged the electricity into the same sort of factories they had before. And that didn't give a very large productivity boost.

But then people spent 30 years to reorganize factories to take advantage of electricity. And the main thing was, you could have a lot smaller motors, many smaller motors instead of a few big motors which you drove power around through some big bands. And then there was huge benefits from electricity once you reorganized factories to take advantage of it, but that was what was required. And so similarly, I would say for remote work, it'll be the reorganization of work around remote work that will make the big productivity gains.

Infovores 07:18

And what do you see as kind of the time horizon for that? I know you mentioned that you wouldn't be surprised if 30 years from now, remote work were the most important trend that people weren't really keyed into fully. Do you think that's still true? Even with AI, if we go out 30 years from now and compare them side by side, will remote work have more impact than AI?

Robin Hanson 07:49

Possibly yeah. You have to envision…what I have in mind for remote work is… so imagine, today a plumber comes to your office, and they are human who come with their bag of tools. In the future, a plumber might be an avatar that sits downstairs in an apartment complex that anybody could use whenever they need it.

And it shows up with a standard set of tools, and then a plumber uses it from long-distance. But then each little step of the plumbing job a different person swaps into the avatar to do so we ended up with as much specialization as you might have as an automobile factory. And as you know, automobile factories are vastly more productive than independent small team of four people putting together a car, because of how much they can specialize in each particular task. And so, if there's firms of 1000 plumber specialists that each would do one little piece of a plumbing job, they can each swap in at their moment when the avatar needs to do that next thing, and they swap into the avatar, and they have to do that task. And now you're getting sort of car factory levels of specialization, in something that today is done by a generalist. That's the kind of productivity gains that I'm seeing as huge. It's the opportunity for specialization. Basically a city’s scale of specialization even in remote places.

Infovores 09:21

Gotcha… specialization and trade is determined by the extent of the market and if you have lots of people that are essentially within the same market, then you can have lots more specialization, lots more gains from trade. I'm not sure I fully understand the plumber example though, because that seems to me like something that is really restricted by physical space. What am I missing there?

Robin Hanson 09:50

Once they have a good enough avatar, they can do it from elsewhere.

Infovores 10:02

Would the avatar have physical character?

Robin Hanson 10:05

The avatar will be a physical robot, basically with arms and actuators and claws. And if it's good enough for the person from long distance to control it with the video and audio, then they can swap in and just do the next step or the physical job that needs to be done. So yeah, you would need a good enough haptics and interface, fast enough internet so that you could just naturally directly control it. But those are coming.

Infovores 10:29

How soon do you think that's coming? This is remote work paired with a lot of hardware advancements as well.

Robin Hanson 10:34

Right. But if there's a large enough industry demand for it, then I think this is well within the reach of current abilities. It's just a matter of doing it. So the AI is much harder job than you're talking here of sort of just physically good enough haptics.

Infovores 10:56

That's fascinating. I guess if we think about it in terms of the advances in self-driving cars for example, it seems like they've come a really long way and some of the biggest obstacles remaining are more regulatory than anything else. Probably something like this with robotic avatars is closer than I was thinking before.

Robin Hanson 11:25

Well obviously regulation could get in the way of this plumber. If local plumbers make really high regulatory requirements and what this avatar has to be capable of, then they could prevent it. But it seems to me enough places might allow it to let it take off. And then other places would be shamed into copying or be left behind being much less productive. With a self-driving car you can imagine, basically the problem is it can help but if you want to have the driver turn off their attention and not be paying attention to the driving, this thing needs to meet really high standards. But we don't have the person at home doing the plumbing and somebody looking over their shoulder replacing it. And so the nice thing about the remote work thing is that it does help automation. That is if you break any plumbing job into 30 different subtasks, you can automate each subtask, one by one, you could figure out which subtasks an automation could do. And then at that point, instead of swapping in a human to do that, you swap in the automation to do it. Because you've broken it down into lots of little things, as opposed to the self-driving car, if it's going to be that it has to do all the tasks, right? It’s not enough for it to do 80% or 95% of them. It has to be ready to do all the tasks. And that's the hard part about that problem.

Infovores 12:42

That makes sense. The plumber is not at high risk of causing a really bad outcome in the tail and killing someone just by repairing a pipe. And so getting it to the stage of good enough to start rolling out and then learning from user feedback and more kind of outside the training world of creating the thing, you could see it take off by capturing one local market at a time maybe and then eventually barriers to adoption in other places just kind of evaporate.

Robin Hanson 13:16

The plumber is just a stand-in for lots of industries where we don't have much specialization because we need somebody pretty close to the final place where it's done. So services that happen in the city actually aren't very specialized. And you're imagining factory-level specializations from all these little local tasks. That's the sort of thing I see a huge payoff from. And automation can swap in there. But I don't think automation is the main part of it, it’s just a nice add-on.

Writing Futurism

Infovores 13:48

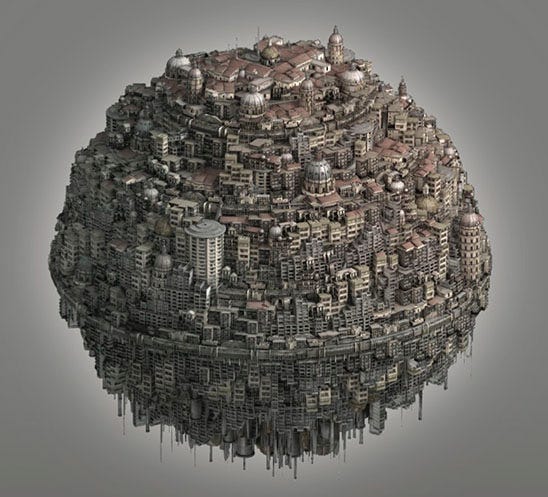

Makes sense. This idea of robotic plumbers and robots doing various other tasks gives a good segue into your 2016 book, which is unlike any other book that I've ever read. It's called “The Age of Em”, and you give this incredibly rich and detailed prediction of what work, love, and life will be like when robots rule the earth.

We will get into some of the specific specific details of how that relates to current things going on in AI. But first, what inspired you to write a book like that so far out into the future 100 years or more and what are the main benefits of thinking through far off future scenarios that inevitably are going to differ from what we predict?

Robin Hanson 14:35

The main goal of that book was to show people that it's possible to do much more detailed futurism than I'd seen done before. So a lot of people sort of say, you just can't do futurism, it's not possible. And so they say, a science fiction story is kind of the best you can do, you might as well be inspired and speculate on the basis of things like that. And I was trying to say, No, you can take a specific scenario and work out a lot of detail carefully if you follow my method, which is a pretty standard, simple method, but it takes somebody knowing a lot to do. And if you believe this claim, then it would be worth having hundreds of books like this, each taking a scenario that has maybe a one in 1000 chance of happening. And by having all the books, you'll cover a lot of scenarios. So each book doesn't need to convince you of a high chance that that scenario will be true. A one in 1000 or a 1% chance is plenty. We can afford to have 1000 books, because we've got lots more than 1000 books in the library even about the future. And so the claim is we can actually study the future, it's quite possible to do so.

And the key thing to do is you define a scenario, let’s say a particular technology that might appear with certain characteristics. And then you just turn the crank and figure out how that plays out in the world. And so you assume the world is much like ours, except it has this new technology. And then you go through all the main fields that we understand applying your standard results in those fields to how would the world change with this technology. So my example of that is brain emulation, i.e. a computer model of a particular brain that would substitute for that brain and have similar behavior. And I assume such a thing could exist and be cheap. And I assume a few things about its features, mainly, that they are simple and not very complicated, and therefore it forces me to have a relatively simple scenario describing them that is, these simulations are black boxes, and you don't know how to take them apart or mix them and match them with others. So all you can do is turn them on, run them fast or slow, copy them, that’s it. And then I say, “okay well, what will the world be like as a result of that change?” And if you apply economics, electrical engineering, structural engineering, urban economics, sociology, you just take every field you can think of, and say, what does the basic 101 version of that field say about this scenario? And just pull those all together to make a consistent combination of them all and ta-da, that's a description of what such a world might look like.

And you might think, yeah but you couldn't do that. And I'm gonna say, but I did it! I did this trying to prove to you that it can be done, it was done, and I hope to inspire other people to do similar efforts.

Infovores 17:44

I can definitely attest that you achieve your aim of constructing something that is very internally consistent, that puts together all these pieces that we've learned over time, and still makes sense even though it's kind of projected onto an imaginary or simulated scenario. I also feel like writing a book like this—apart from it being such low hanging fruit, since you have millions of books about history in the past, and there's pretty severe diminishing returns to another book like that, in comparison to the very few books that look at the future with a similar level of almost historian-level detail—but there's also some interesting kind of advantages to this kind of style or art form that I was curious to ask you about.

So it seems like in a lot of situations, it's very difficult to get an audience interested in understanding basic facts about how human life is right now. If it's not new stuff, if it's not urgent like a brand new breakthrough, it doesn't catch people's attention in the way that kind of the gradual build up of human knowledge across a lot of different fields does, and so framing it as “I'm writing a book about the future”, but then including all these things that are, in my mind, super relevant to the world that we already live in that I hadn't really thought of before, it’s kind of a cool way to market understanding that's already relevant now.

A related point is that I think a lot of people are too enmeshed in the details of their social life and there are things that they take for granted intuitively in interacting with other people, that they're actually not very receptive to being told that they're a particular way, even if that could be very well supported. A lot of the theories that you have about how people behave make a lot of sense, but people don't like listening to them. But then in this future scenario, all of that resistance kind of evaporates because it's like, “he's not really talking about me and saying that I'm like this, I'm signaling or I'm status-conscious, or whatever. He's saying that these robots are like that. Did that figure into your thought writing this at all? Is this an opportunity to tell people to some extent how they already are?

Robin Hanson 20:31

I mean, I didn't plan it. It didn't influence my plans. But I certainly noticed and other people notice that this could be more of a tutorial about how the world works. I've certainly noticed that people are just too interested in changes relative to the constant. That is, a lot of people are eager to look at news about trends and how things might be different a little bit in the future. And they're less interested to know that you don't understand the present, you don't understand the basic world you're in now very well. Why are you so interested in how it might change in five years? You should be more interested in just knowing about this thing you're in that you don't understand. So I think people do tend to assume that because they can navigate the world effectively that they understand it. I mean it’s also a thing in history that good history analyses will focus on theories about how things work that you might realize apply to you too. And you can learn about your world from history as well.

Infovores 21:33

If you had to put a number on this, what percentage of Age of Em would you say pretty much directly translates to social life today?

Robin Hanson 21:45

I guess I'd have to go through and do a survey, but I would think at least 30%, maybe 30-70%? I guess I'd have to look more carefully. There's certainly some things that are different. I mean, I tried to find the things where there were differences and trace those out. But even the differences highlight things about today by contrast.

What “Ems” Are Like

Infovores 22:07

Of course, that makes sense. And so right in line with that, the robots in Age of Em retain some very human features. They're based on high fidelity brain scans from actual humans, and so they still socialize and have desires for things we care about in terms of romance, belonging, success, all of these things. It's very familiar in that sense. But I'm wondering, in general terms, what criteria you looked for to determine whether certain human features get kept versus others that get abandoned. And based on that framework, whether there are any major human features you see as more or less likely to change in a possible AGI future, if that were to happen before, or instead of, the Em scenario that you envision.

Robin Hanson 23:07

So you're right that I need some sense of which features are how pliable or plastic in order to project the future. That is, some features are just so hard to change that I kind of assume they stay constant. Maybe their expression or application changes. And then other features are more ready to change if the world wants it.

So part of that is just looking at the history. Which are the features that have been most constant across our past, and which things have changed a lot across space and time? Whatever has changed a lot in the past is a candidate for something that could also change in the future. And then I'm also using our theories about which things are deep and hard to change versus on the surface and ready to change. If we could pick concrete examples, I guess we could talk about, I don't know, work hours or something. And clearly, work hours have changed over history. So ems could work more than we do today because our ancestors worked more than we did at least in certain time periods. But pretty much all work in the past people needed breaks, breaks every few hours, breaks at lunch, breaks in the evening, breaks on the weekend. That seems robust. So then I presume ems will need breaks. They may do different things with them perhaps, but one big clue is just what has been pretty consistent in the past.

Infovores 24:37

You say that ems will be good advice givers, to give a concrete example of a human... actually I'm not sure if that would be considered a good human feature or not… But I'm wondering, if the ems are good advice givers, will AI necessarily be a good advice giver? And what are your thoughts on AI to human mentorship possibilities? Even just in the immediate future with GPT.

Robin Hanson 25:06

Well, the whole idea of ems is that they are really close to being humans. So we know a lot about humans, and we can use all the things we know about humans to talk about ems. Ems are only a modest modification of a human.

AI is a name for a vast category of possible computing and machine systems. And you have to pause to realize just how vast is the space of possible systems. If you started out with a human and say, AI must be something like a human but not that different, you'll just be really wrong. The space of possible AI is really, really large. And that's one of the things you have to learn to understand about AI—AI is just a name for this vast space of possibilities. So that's one of the biggest problems and reasoning about AI is to try to categorize it somehow, to make some shape of the space of possibilities to draw some lines through it or playing through it so that you can distinguish, like what are the main types of them. So that's why if you ask me, are AIs good at advice, I go well, some are and some aren’t. It depends on what assumptions we are making about the kind of AIs.

So in that case, I might just look more to the human. If we're talking about AIs advising humans, the constant there is the human. So I might say, when do humans want advice? When are humans willing to listen to advice? That would be the analysis base I could go on. And now we might say, when could AI fill the slot that humans want for advice? If we look at humans who take advice, we see that often, humans asking for advice or taking advice is just a way to suck up to people basically. So this anecdote from a book I once saw, struck me, which was, there's this high-level manager at some firm. And one of the things that happens to high-level managers, people are constantly asking for meetings with them coming in, asking them for advice. That's the thing high-level managers do all the time. And so this person announced that they were retiring in six months. And immediately, nobody wanted their advice anymore. They're the same person knowing the same things. But nobody wanted advice, because in fact, asking for advice is really kind of a way to ask for social support. They wanted his alliance, they wanted him to support them, you see, and all of a sudden he was no longer a valuable supporter, because he was going to retire and therefore they didn't want his advice. So that theory of advice says that AIs aren't going to be very useful as advice givers until they have power, so that you can pretend to solicit their support by asking for their advice. Because it's not really about the advice.

And then we also noticed that humans often try to give advice as a way to exercise dominance, which is often a reason why people resist advice. People are like, usually pushing advice on other people who don't want it. That's just a really common thing in our private interactions. And so it's not about me begging you to give you to give me advice, and you like reluctantly turning your head to me and maybe helping me. It's about people constantly pushing advice on each other. And people trying to be polite about it, trying to pretend they're listening, and then also trying to show their independence and that they aren't taking the advice from everybody who pushes it on them. So that scenario says that AIs will have to have some social power in order to push their advice. And then maybe they could push people to take it because of the same reason humans take other people's advice, but it's not about actually wanting the information. It's more about a social dominance display of, people are dominant if they can get other people to take their advice. So, for example, managers and politicians often resist taking advice in public even if they take it in private. That is, they'll often want advisors to advise them in private but if somebody gives public advice they go out of their way to not do that thing. Because that would make them look submissive to this other person who gave the advice. So now if you put all this together with AI we say, AI doesn't count for advice until it has some social power. And otherwise, people aren't going to want it.

Infovores 29:28

So it seems like one question is, to your point in the book, are ems good advice givers or are they just better advice receivers? Because in the situation that you describe in the book, a lot of what's going on is ems are receiving advice from other copies of themselves that have different life experiences, but are fundamentally linked in that way. And so they have a lot to gain from asking for advice, because it's very applicable to their specific idiosyncrasies.

Robin Hanson 30:14

But they’re not competing, having dominance contests with other copies of themselves, that's more the presumption here. Say you're a dentist and your twin brother's a dentist and you live in different counties right? Now you might be willing to call up your twin brother and get his private advice about being a dentist, especially if his practice is a lot like yours. If you saw him as your ally, and the one person in the world you most loved and were closest to, then you could be asking him for advice. And he could be giving you advice, if his world is actually a lot like yours, and he's actually a lot like you, that's the situation of the ems. They're giving advice to very closely similar people in very closely similar circumstances, they're giving it privately, and they're not in a dominance competition with each other.

Infovores 31:04

And it's also much easier just at an informational level to interpret a request for advice, because I feel like if I sincerely really do want advice, and I want to apply it in order to improve, I know that, but the person I'm asking for advice is thinking, are they trying to ingratiate themselves with me? Are they trying to present themselves in a particular way? What's kind of the ulterior motive? Whereas it's much easier to to interpret and understand the intentions of an em copy.

Robin Hanson 31:38

Actually what I say in the book is that people will look at the experiences of people close to them, which is a little different than asking for advice. So imagine you have a marriage with your spouse, and there's a copy of you who is married to another copy of your spouse. Now, if they did something that got them in trouble with their spouse, that's information to you about what might get you in trouble with your spouse. They don't need to actually give you advice you see, but they're in just a very similar situation. So you'll just be very interested in what happens when they do things, because that'll be informative about what happens when you do things.

Infovores 32:16

That seems related to a paper you wrote with Tyler Cowen about… I remember one of the points in this article about why people disagree. And basically, one thing that stuck with me from that is that if you if you know that someone else has the same priors as you and that they also hold a particular belief, you should update to believe something similar to what they believe, even in the absence of any sort of explanation or seeing the evidence yourself.

Robin Hanson 32:53

Sure. At least, on average, you should move to their position, sometimes less, sometimes far. But on average, you should be moving to where they are.

Infovores 33:01

And it seems like among among a tribe of ems that are all copies of of each other, but different experiences, it's very easy to, without having to ask explicitly, you just see what they're doing and learn a lot of things about what they believe based on their context, and you can update very quickly.

Robin Hanson 33:23

So humans today have many kinds of social groups that they’re a part of. And then this set of all the copies of the same original, which I call a clan, is a new social unit in the em world. And so we're somewhat speculating about this new unit. So the client itself will try to make this unit bond as closely as you would bond with yourself at different times, or you with your twin brother or something. The question is, how well they'll succeed at that. And, the more that you will compete with other people in your clan, the more that you'll start to see them as rivals and maybe distrust them and maybe not be entirely honest with them. And if there's play in leadership positions, maybe that's unavoidable there will be some conflict, but I think the clan would go a long way to try to suppress that. So for example, if you can hear your clan members in your head as a voice, but you don't like see them as a body in front of you, that could help because we often trust ourselves as a voice in our own head, and a body in front of us we might more see as a rival. And they would try to avoid being in situations where they compete with each other for the same roles. And that would make them feel more like they were just part of the same person, basically. But it's an open question how far they'll succeed. That's something we don't know, because we haven't actually seen that. But there's a sense in which clans have just a lot more ability to be close than most of our other units, because they are actually very similar to each other. And they do actually share a lot of interests. And so it can be structured that their interests are really quite well liked. But is that good enough? I don't know.

Infovores 35:05

When I discussed the notion of em copies with a friend, something that came to his mind is how in science fiction movies, sometimes you have plotlines were a group of clones kills another group of clones. They're the same genetic material, you would think that they should be grouping together as a clan as you talk about, but actually they turn very violent. And I wonder wonder why it is that you don’t put more weight on that possibility in the book?

Or to give a related example, why should there be any em vacations or em leisure in equilibrium? Because the person who has the same capabilities that has a copy of you could they exploit your leisure time. Any leisure time that you have, they have an incentive to exploit and kind of cut you out in some way by taking your position. Or what am I missing there?

Robin Hanson 36:15

Well fiction is always going to be highlighting conflict in the most dramatic forms. That's just a generic formula for science fiction. So even if you look at the Black Mirror TV series that explores various future technologies, it is pretty much always trying to find the worst possible scenario with the worst possible conflict for any tech, right? It's not a very good guide to whether such tech would actually be good or not because it's basically always trying to find the worst case.

So ask yourself how much conflict you have internally to yourself across time. So we do have some conflicts, you might rather spend money now and leave it to your future self to make up the difference. Or take advantage of some fun now that you could have that your future self will suffer from. And we mostly limit that sort of interpersonal conflict by sort of a shared sense of identity— you see that future person as you and you see that if you hurt that future person, you're hurting yourself. And that doesn't seem so fun. And so that shows there this possibility of producing more coordination and cooperation if you see these other ems as yourself. And so we can predict that they will try to do that. And the question is just how far can they go? Obviously, they won't always succeed. But it seems clear that if they can succeed, then the ones that succeed will win. The clones that are killing each other and exploiting each other all the time, well that's just not a very winning formula for being a successful clan. They will die out.

So basically, the em world does select for personalities to get along with themselves. There are sometimes drama people where there can only be one drama person in the room, right? They're the drama person, and the drama always has to be about them. And their story has to be the center of attention. Those people don't get along well with themselves. If you have them in the room, they're fighting over who is the center of attention in the room, right? That doesn't work so well in the em world, as the world needs a lot of coordination with people like yourself. So it's more rewarding people who get along with themselves, people who can cooperate with themselves. But just like our world doesn't really that much reward people who can't save for the future, who can't delay gratification, the people who exploit the future self by taking all the advantage right now and spending every penny in their bank account. They don't survive in our world very well. You could just ask, why does anybody ever work because they could have fun now and let their future self work.

Infovores 39:06

Yeah, so it definitely seems like the em world is selecting much more strongly on being able to delay gratification, patience, and doing what makes sense in the long term versus the immediate short term benefit. And this is part of a broader argument in your book that we've been living in a sort of dreamlike state where there actually hasn't been very much selection pressure among humans for the last several centuries. At least in recent times, it seems like part of the reason for that is, as liberal societies develop, and as richer societies emerge, we seem to be more concerned about making sure that people don't get selected out, making sure that welfare is provided to people who maybe are not very productive or are even clearly causing problems, negative externalities. But we still feel like it's a basic sort of human right to ensure some level of preservation regardless of people's choices, except in some rare exceptions.

What makes you think that ems won't feel that sort of impulse? Is it just a function of the ems being paid at basically subsistence levels in your scenario or what is the main reason why selection pressure will return with a force?

Robin Hanson 40:51

So in our world today, we still have pretty strong selection pressure on businesses. Businesses you can create pretty quickly, they can grow quickly, they can die quickly. And we don't actually prevent them from dying by saying, “Oh, we're so sorry for you, we will subsidize you in order to prevent you from dying.” So there are big parts of our world where we allow fierce and severe competition. It's also true in say, democratic elections. We allow candidates to be voted out of office, and we don't feel very sorry for them and make sure they get an office to stay in indefinitely. We allow severe competition among candidates for office. And similarly, in music or movies, we just have pretty severe competition. For artists or music, we don't feel sorry for musicians, and make sure they all have enough people hearing them in order to be respected as a musician. If people don't like your music, we are allowed to have nobody listen to your music and even make fun of you. That's part of what we allow.

So it's only a limited range of things where we don't allow as much competition and in the em world, there's just naturally more competition for population, because they can just make population much easier and they can also make population go away. But it's just mechanically much easier to make ems, and mechanically much easier to end them or at least put them in a retirement stage. So for example, you might feel sorry for ems enough that they don't die. But if you can just make them retire at a really slow speed, they're not dying. And so now, maybe you don't feel so sorry about them retiring, right? So I can imagine people say, let's make sure nobody ever has to die, let's make sure the worst that ever happened to anybody is they retired to say 1/1000 of a human’s life speed. That's really cheap. And so now, okay fine, that's the worst it can get. But we still allow enormous competition for who gets to run faster. And then it's all about how fast you live. And then we'd allow that, right? If you had a sympathy, “no, everybody needs to run at the same speed, we would all like people running at different speeds.” Now, you're just gonna have a lot more regulation in society. And so a fundamental dynamic now and then is really just how many elements of society are we going to allow competition on? How much are we going to prevent competition? And that's in part sort of how much we are embedded in a larger competition.

So up until recently, the world was embedded in competition between nations and societies. And so if one nation was very kind to its members in a way that was not very productive, it would lose out over time to the other nations. And that was a discipline that limited how bad things could get in various dimensions. Today, we have more of an integrated world where, in fact, we don't have so much competition between nations and we more have a unified world community that if it creates a rule that is adopted everywhere in the world, then it could overturn competition and we have gone that way for some forms of regulation. But I'm basically assuming in this analysis that doesn't happen in the em world. But there substantial competition is allowed and it has these effects. Now, partly that's because of my method of analysis. One of the main reasons I'm able to say so much about the world of the Age of Em is that I assume it's competitive. And competitive worlds just tell you what happens. In a non-competitive world, the world of rich people who are full of leisure and can do whatever they want, it's not enough to just know how rich they are, what technologies they have to know what happens, you have to know what they want. But in a competitive world, you don't actually have to know what people want to know what they do. Because they do what they have to do to win the competition.

So if you ask what kind of movies would Hollywood make? If you have a world where Hollywood has a government monopoly, where they are the only ones allowed to make movies and they can make whatever movies they want, then the movies Hollywood makes is whatever the executives want them to make, right? But in a world where the public decides which movies get sold, and if you keep making movies that don't sell you go out of business, then we can predict the movies that are made are the movies that the public wants. And we don't really need to know what the executives want. Their preferences are not very relevant. It's the public that decides what movies get made. And I'm using that method of analysis in the world of ems, I'm saying this is a competitive world, and therefore I can figure out what they do, and I don't need to know what they want.

Infovores 45:31

That makes sense. And even in our world today, which is much less competitive in comparison to the age of Em, there's only a relatively small number of dimensions where people are actually really concerned about alleviating inequalities. So a lot of focus is put on income inequality, but there are lots of inequalities that are arguably even larger that are pretty much never talked about.

Robin Hanson 46:06

So even income inequality we don't do that much about.

Frozen Brains and Em Gender Dynamics

Infovores 46:10

Right. So to mix things up a little bit, let's try playing a game I call “how to change my mind”. I'll throw out something relating to views that you have espoused and you can tell me the conditions that would make you open to reconsidering your position. How does that sound?

Robin Hanson 46:30

Ok, I may have to pause.

Infovores 46:32

Sure, no rush. So the first one: you plan to have your brain frozen after you die, so that it can be emulated into a future version of you. This would be once the ems arrived. What, if anything, would convince you to change that plan?

Robin Hanson 46:48

Well it's based on a cost benefit trade-off. Certainly, if the price of freezing myself went way up that might tip me over, or if the benefit went way down. So the two main risks are that the kind of information that's preserved in a current freezing of a brain is just not sufficient. If you could show me that, contrary to my current impressions, the actual information is coded on a very fine spatial scale with very fragile structures that are quickly destroyed in a freezing process, then I'd say, I guess it doesn't work, the structure is not there. The other risk is just that the organizations won't survive. So if you can convince me that they're going to face some hostile opposition that’s just gonna try to destroy them and probably will, then okay I guess the organization can't last. So then I wouldn't last.

Infovores 47:37

People often use the phrase, “the future is female.” But Age of Em actually implies that the future is largely male.

Robin Hanson 47:45

Does it?

Infovores 47:50

In your section on business, I think you talk about people whose qualities tend to be most competitive today, who tend to be the most productive, and work the most hours. And on kind of right tail of the distribution, a lot of those people are male.

Robin Hanson 48:11

So I describe two contrary factors, and I'm not sure which one dominates. So one factor is certainly that men tend to have higher variance in productivity. So the most productive people in each area tend to be men. That's one factor. But the other factor is, as I say in the book, that women tend to do better on raw sort of grit and determination and persistence in difficult situations, where men will often lie down and die, or quit, or just be lazy, and slovenly and unmotivated. Women will just keep plowing through. And the question is, how much that matters.

We will select the highest performance, but you see men often have this highest performance because they get a lot of social benefits and celebration from it, right? Men often get more girlfriends and wives and praise for being the best. But the em world will select the best, and then they'll be ordinary in that world. So can they be motivated to be the best when they aren't distinguished and they aren't celebrated? They are just existing because they're the best. But that's it. That's all they get: just existence. If men are demotivated then if they say, what's the point of working so hard to be the best if I'm just average? Then if em women are more willing to just keep working hard even if they're not celebrated, then maybe women will have an edge there. That's the question.

Infovores 49:59

What do you think the ideal gender mix is to have in an em clan, if you had to guess in that case, because I'm wondering whether all women might band together better in some ways, because of..

Robin Hanson 50:15

Well, the idea of a clan is all copies of the same original person. So they would all be one gender, unless they do some sort of gender transformation within the clan.

Infovores 50:24

So do you think male clones will get along better or worse than female clones? Or will there be any mixing at all?

Robin Hanson 50:31

I would think that the more similar are clan members to each other, the better they get along. Because we're going to what we're going to try to do is make them feel like they're just each other in their head. It's like I'm just hearing myself talking to myself, basically. If that's what the image we're going for, then they should be as similar in as many ways as possible. So if you have yourself talking in your head, except it's the other gender, that might be a little disorienting, sort of break the illusion that it's you talking to yourself.

But I do think probably most people want to do a male female pair bond. That's just a pretty common human preference. So that would be my assumption is most people just for deep human emotional reasons want to be part of a male-female pair bond. And so they will do what it takes to make that happen. And we will pay substantial costs in order to make that happen, so that's probably how it happens.

I tried to discuss how you can have that be true, even with an unequal demand for male and female labor, by basically having different numbers of copies of each side of the relation or different speeds so that they can have the same sort of equal relationship with each other, even if they have an unequal relationship with the labor market. But, obviously, the simplest way is just a nearly equal domestic labor demand. But I think you can accommodate maybe a factor of two or four in the ratio difference through some other means.

AI Sentience, Em Religion, and Human Rights

Infovores 52:04

Gotcha. What do you think are the odds that we look back on Blake Lemoine and in some way, kind of see him as being one of the first people who really understood something about AI?

Robin Hanson 52:20

I’m sorry, Blake who?

Infovores 52:25

Blake Lemoine was a Google developer who basically was telling everyone that AI was sentient. He got fired about a year or so ago, before the excitement that we're seeing about AI today. Do you think there's any chance that people look more favorably on him in the future, rather than just as a crazy person?

Robin Hanson 52:46

So far, people have just made this sharp distinction between humans and machines and animals. And when they make that sharp distinction, they're willing to just be much more harsh in their treatment of non-humans than humans, right? And so simply focus on animals, right? The more you start to see animals as continuous with humans, say chimpanzees, then the less willing you are to tolerate harsh treatment of chimpanzees. And the more that you're going to insist that people be kind in various ways to the chimpanzees. Presumably, we're eventually going to do that for machines, too. And so the question is, how will we draw the lines?

That is, well, we just have some graded treatment where you can slowly treat them more harshly as they get different from humans, or we draw some sharp lines is a past this line, you can ignore it because that's nothing. And that's just going to be hard. Especially with AI because again, there's this much larger space of possible AI than there is for animals even right the space of animals and compared to humans is relatively limited in their the space of possible AI. So, the nature of morality and the sacred is such that you tend to want to have relatively simple clean rules that everybody can observe and enforce. And the question is, well, what can those be?

So, there's two kinds of sets of rules, one set of rules is how not to be mean and cruel. And maybe another set of rules is how much support and help. So even in the past, if you don't have any sort of welfare or obligation to save somebody else who's like dying in the desert or something, you can still have norms about not mistreating them when you come across them, so it will be easier to just set up norms of avoiding mistreatment than it will be the norms of help. So a basic problem with ems and AI is it's just so easy to create them that if you have an obligation to help them once they're created, this is just unsupportable. It's just too big a demand. It's just easy to create things that if there was an obligation to help them then they would just quickly suck up all available resources to help them because they're so easy to create. So either you prevent their creation, or you don't have such a strong obligation to help.

But you can still enforce mistreatment rules, where if you create it, you don't do the following things. That's more feasible as a set of rules in a world where ems are easy to create. And now the question is what counts as mistreatment? And one standard we have is some sort of voluntary standard, like if they object, then you're mistreating them. But if they say it's okay, maybe you're not depending on what the rest of us think. And you could certainly imagine in the age of em, one simple rule you could imagine that applies to a very wide set of cases, is just a right to suicide. You say look, pretty much any em and maybe any AI should just be given the right to suicide. If you understand the concept of suicide, and you decide that's what you want right now, okay, it's yours. And that can also be a way to define torture, right? What's torture? Well, if they'd rather commit suicide than continue existing, you must be treating them pretty bad.

We're searching for simple rules that we can all agree on to apply in this really vast space of possible creatures, that's the hard problem here. And we haven't really explored that space for which we don't have much of a sense of how big it is, and what all the features in it are, and what they could be like. I mean, obviously, some of them could even like torture, some of them could enjoy suicide. How do you apply rules to them?

Infovores 57:01

For a very long time, in Western societies, the Bible has been a really foundational, the foundational book I would say, and that affects so much of how people think about things in ways both conscious and unconscious. Will the ems still have any connection to the Bible? Or will they perhaps develop an alternative bible of some sort? Will there be like a Good Samaritan story, except the good guy is the one who walks by the em on the road to Jericho without mistreating them? What do you think that looks like?

Robin Hanson 57:46

So the two big facts to notice, or maybe three, like one, clearly, religion was very functional in the farming era. I mean, the modern religion showed up halfway through the farming era, and before that, they had some pretty different religions. But, for the last few thousand years, we've had the modern religions, and they have been pretty functional. And the industrial revolution happened, and they survived it all. The major religions are still the major religions in the world, even after this enormous transformation in the industrial revolution. So if the Em revolution isn't any bigger of a transformation than the Industrial Revolution, you’ve got to predict whether they can survive that too. Now, what we have seen is a great decline in the interest of religion in general, over the last few centuries, but we still have the same religions being the major religions. I mean, if you're going to do religion, you're going to do it the old way, in our world. And so I would predict that if the Ems want to do religion, they'll do it the same old religions and those religions have already shown that great ability to adapt to changing circumstances because that's what they did over the last few hundred years, so they'll probably be fine at adapting to these new changes. Then the question is really just how much demand for religion would Ems have? And for that, you need to try to understand, well, why have we had a declining interest in religion in the last few centuries? Because we have pretty strong interests before. And for that, I have this sort of forager to farmer to foragers story as my explanation of the trends in the last few centuries. And that theory predicts that we would want to return to religion with animals, because they would be much poorer and need a lot more self control and dealing with hard circumstances. And religion would be there for them for that. And so my prediction is okay, they go back to emphasizing religion more, and they use the traditional existing religions, because those seem pretty robust. And that's the simple prediction. Now, you can already predict, you'll need a few modifications to traditional religious dogma in order to accommodate the Ems, but they're pretty obvious and easy. So of course, yeah, they just switch, Ems, they say, ems are children of God, ems have souls, ems can go to heaven. Now the question is, if you make a five minute copy of an em does it go to heaven?

Infovores 1:00:13

Right, so these are like the theological debates in the age of ems.

Robin Hanson 1:00:15

Or if you make a copy and it sins, is that your sin? Or is that the copy’s sin? Because the law will actually have to make a decision there that if you make a short term copy, and it sins, it breaks the law, that's your fault. That is you will be held responsible for the legal violations of short-term copies. And I think if the law does that, the religion will probably go along and call that a sin too. So if you make a copy that commits a sin, that's your sin. That's my guess, because it fits with the law.

But those are the questions that we'll have to answer in order to adapt religion to it, but again religion has adapted so well to the modern world. It's really pretty flexible, so I expect it will continue to be flexible. Logical consistency has never been the main reason people got into religion anyway in the first place. And theologians have long been able to tell twisted stories to try to make things that appear inconsistent be consistent, so there's gonna be plenty more of them. So they'll just do that.

Infovores 1:01:14

The thing I was hung up on there for a second is, without physical bodies, in principle, ems could go on indefinitely. And so if ems are already immortal, does religion like… is that really such an easy hole to plug? Or how do you…

Robin Hanson 1:01:35

That's a framing question right. So you can imagine that every five minutes, a copy of you goes off to a heaven even if you continue. Or you can imagine only some end point of you that never continues would go to heaven. Those are two different religious choices that theology can have right? Or something in between.

That's a key question. So I don't know. I guess the conservative thing is to say, only a branch that ends goes to heaven. But maybe does a five minute branch that ends go to heaven? Does it go to a slow heaven? You get into fast heaven if you live longer? Those are the tough choices there, right?

Infovores 1:02:17

You could imagine roping in maybe a theology of suicide since suicide is not frowned upon in the same way in em society, maybe ems commit suicide occasionally on faith that they will be transcended into something beyond, into heaven.

Robin Hanson 1:02:37

Right, but if they commit suicide with one copy that was branched off and then the mainline goes on, does that count as suicide?

Infovores 1:02:43

That debate still remains as well. Maybe you're not showing enough faith if you if it's only a short-term copy.

Robin Hanson 1:02:55

So maybe you need to have sacrificed and suffered for a long enough time to qualify for heaven or hell or whatever, I don't know. But the point is, religion will just search in the space of possible answers and they will compete with each other and some will win the competition because they more motivate people and bond people together and we can understand the underlying function of religion as staying constant while the details vary.

Infovores 1:03:27

Fascinating. So I guess I'd like to close with just a couple of miscellaneous questions. So just very practically, how do you use GPT? Like, what have you found to be the most valuable applications of it for what you do and what insights would you have to share with others?

Robin Hanson 1:04:00

So at the higher meta level, my attitude is that we've seen rapid improvement in abilities over the last few years and that we’re plausibly going to hit a knee of the curve in the near future, where they won’t improve as fast–they’ll run out of data, run out of hardware. And so we're seeing rapid improvements, but they'll reach some plateau sometime soon, and then they’ll be stuck near that plateau for a while. If that's true, then the time to really pay close attention to their abilities is when they hit that knee and go into the plateau. If they're rapidly changing in abilities, then looking at the limitations of any current version isn't very informative about the future, because they're going to change. You can look at what they can do, but looking at what they can't do won't tell you that much.

Then the thing to ask today is what can they do in a robust way? So what I did is I did some tests to see like, what kinds of reasoning can they do or not? In closer to my area, what kind of exam questions they can answer for my students, because maybe my students will try to use it to answer my exams. And I saw that it was impressive in terms of what it can do compared to previous systems, but it's just not good enough to do a lot of the ordinary tasks I gave it. And I can see how to sort of assign my exam questions so as to avoid its ability so that I'm safe from people using it to take exams. I can't see that many other ways I could personally use it. But maybe in the future, it will be better. But the point is to get a rough guess now and wait and do the extra effort when it reaches the plateau.

The other thing I should be doing is just listening and saying, what do I hear about who can use it to do what? And the main thing I hear is that programmers use Copilot to program and I know some experienced programmers who are saying they're getting like a 20% boost in productivity from using Copilot and I go, okay I believe them. And that's plausibly the biggest valuable application for it. If I try to think about what applications that could work for, that just makes sense as an application that would be high-value. So at the moment, that's my best guess about what’s going to be the highest value application. And if now it’s 20%, maybe it'll go up to 40%, probably it won't get that much higher. That's roughly the boost that you're gonna see out of it. That's the main group of users and how they'll use it. And that's my tentative conclusion. But again, I'm going to wait till I see them hit the knee of the curve. And I'll try all my suite of questions again, I'll see okay, have you figured out how to do the following questions and what can you do? And maybe it'll be better enough then that I'll think more about what more can it do but at the moment is just not good enough to do the range of things I’ve tried to have it do. But apparently, it's good enough for doing code so great for the coders. I'm not a coder.

[laughter]

Infovores 1:07:10

Gotcha. Yeah, I've definitely been dabbling with copilot. Unfortunately, it doesn't do Stata, which is the main thing that I do.

Robin Hanson 1:07:22

Not yet, but maybe in a few months they will.

Infovores 1:07:25

And I think it'll make it a lot easier for me to use my knowledge of Python, even though it's not my strongest language, because I know enough to take advice from AI. Yeah, that makes sense.

So last question… I mentioned at the beginning of the interview that you recently moved Overcoming Bias to Substack. What all went into that decision, and what do you what to you makes Substack a superior option over blogging as it existed before?

Robin Hanson 1:08:08

I think the main thing that happens when people move support systems or computing environments, is just that support declines for an old thing and rises for a new thing. That is, there's just a lot of value in using a supported system, a system that other people are using where there's people who are building or just fixing the old ones when they break. The more that you're stuck with old computing systems, the more your hardware options are limited and your feature options are limited. And then when things break, it's hard to fix them. That's just the nature of using old things.

So there's a sense in which, for many kinds of computing applications, many people would just be better off if they just kept the old systems and didn't keep touching the new systems. Because there's all these people who just have to keep switching every time old systems go away, and new things come and they aren't actually getting better service from the new systems, they’re just getting the basics of having a system that’s supported and works. So that's the main thing I'm getting from switching to Substack is like, the thing I've been doing before hasn't been so supported, because it was old. And lots of people are using sub specs, if I use the same thing lots of other people are using, I'll get support, right? I can talk to other people about what they're doing, and they can give you recommendations and somebody's fixing the bugs and upgrading the hardware. That's just the sort of thing you get with a supportive system. I know many people who have very happily used old systems, and then they gradually have to switch, not because the new system has any better features or things just because it's hard to keep using old unsupported systems.

Infovores 1:09:59

Bryan Caplan has pretty much been evangelizing Substack since he moved from his old setup to there. And he just says that so many more people are reading his posts on a regular basis than before.

Robin Hanson 1:10:16

That's part of the infrastructure, right? They have an infrastructure to help people find it and read things in the same environment. And that’s of course, what they're designing. But that's part of being in a supported system. People find you more easily there because people go to supported systems to look for things.

Infovores 1:10:33

If you had to predict a year from now, what multiplier would you would you expect to see in your existing readership?

Robin Hanson 1:10:50

Readership is another part of the losing support because I lost my stats on how many readers I had. That's part of the features I was no longer getting with the old system is even knowing how many readers. So at least now I'll know how many readers I have.

Infovores 1:11:06

Well, I'm sure it will be a huge success and I look forward to continuing to read your posts. Thank you so much for sharing some of your insights today, and I encourage everybody to check out “The Age of Em”.

Robin Hanson 1:11:23

Well, thank you. Thanks for discussing it. So last thing I’ll say, I just went to University of Chicago where I did three events. One was a Night Owls thing where I was interviewed on the topic of the sacred, that had like 175 people there.2

Then I did a talk and discussion about "Elephant in the Brain" with about 25 people. And then I did another one with “Age of Em” that had about five people. So not so many people were drawn to the topic of Age of Em there compared to the other topics. But because I gave that talk two weeks ago, I reviewed Age of Em. And so I was all prepared to talk to you about it, because I had gone through it in my head. So thank you for revising a topic here that not so many people wanted to come to a talk on.

Infovores 1:12:10

Well, I think it's definitely underrated in that case. That's… I think I've only scratched the surface of fully internalizing some of the some of the things in that book. And I suspect it'll continue to be very relevant.

Robin Hanson 1:12:24

One thing you could say is that it gives you a more validated mark of how weird the future might possibly be. That is, usually the world doesn't seem so strange and we get used to it. And science fiction tries to make these really strange futures in order to make it dramatic. And you might think, yeah but how strange would the future be, really? And so this is a certain degree of strangeness, you have to admit, right? And it's plausibly about roughly how strange you should expect the future to be, even if my scenario doesn't apply.

Infovores 1:12:55

Absolutely, and a lot of insights into things that are going on all around us right now as well. I think the present is maybe more strange than people realize, and maybe when they imagine the future it's not grounded enough in the things that are likely to persist.

Robin Hanson 1:13:13

And they don't know all the things we don't know about our world today.

Infovores 1:13:17

Absolutely.

Robin Hanson 1:13:19

All right. Well, nice talking.

Infovores 1:13:21

Likewise, thank you for your time.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, check out my other writing at Infovores Newsletter. You can also follow @ageofinfovores to keep up with me.

And make sure to subscribe to Robin’s Overcoming Bias, now on Substack!

The original version used in the email send-out only included a short excerpt, while linking to the full transcript in a separate post, in part because it exceeded limits on email length. These are now combined into just one post.

See here for Robin’s fascinating writings on this topic. The Night Owls discussion referenced above is also very good.

When Robots Rule The Earth: An Interview with Robin Hanson